Web Front-end

Web Front-end

HTML Tutorial

HTML Tutorial

Preview of new features of XHTML 2.0_HTML/Xhtml_Web page production

Preview of new features of XHTML 2.0_HTML/Xhtml_Web page production

Preview of new features of XHTML 2.0_HTML/Xhtml_Web page production

Profit from this richer content structure until browsers can handle the next generation of XHTML

The XHTML 2 specification is not yet complete, but it already has many advantages over XHTML 1, including richer structural features, which make XHTML 2 an editing format better able to serve as the central model for a single resource publishing system than its predecessor. . Perform large or small releases

Profit from this richer content structure before browsers can handle the next generation of XHTML

The XHTML 2 specification is not yet complete, but it already has many advantages over XHTML 1, including Including richer structural features, XHTML 2 as an editing format will serve as a better than its predecessor as the central model for a single resource publishing system. People running large or small releases can start using the new features of XHTML 2 now without having to wait for browsers to provide support for its new user interface features.

About a year ago, an industry standards group asked me to describe how XHTML2 might be useful to publishers. I didn't know if it would be practical, but they offered to cover the cost of going to New York, so I decided to look into it.

The research I did didn’t require a lot of effort. XHTML 2 adds a richer structure to XHTML, making it a format that can be used to create and store content, not just to deliver content to the browser. I'm exaggerating a bit when I say XHTML 2 is already useful; many shops have some very sensible policies for this unfinished standard, and XHTML 2 is still in the Working Draft stage (more info on , see Resources). Unlike almost all HTML-related standards, XHTML 2 is able to provide a lot of value before well-known browsers support it, because it is more likely to store content in a richer and more complex structure. Doesn't deviate too much from familiar HTML elements and attributes.

The Current State of XHTML: Where Are We Now

The W3C XHTML 1.0 standard creates an XML version of HTML. While browsers aren't overly particular about whether a Web page is well-formed XML, Web site designers who are tired of having to do one thing for Firefox and another for Microsoft™ Internet Explorer are seeing more changes in standards. Much value. Many open source CSS collections (such as Open Web Design and Open Source Web Design, see Resources for links to both) have their stylesheets using XHTML 1 sample files for demonstration purposes, and I've heard of some that are barely known to be well-formed Web designers are proud to claim that their sites are built with XHTML. As Internet Explorer and Firefox support more and more CSS features, these Web designers are adding more design techniques to CSS style sheets, leaving simpler and more straightforward (and easier to reuse) XHTML in the basic document .

XHTML 1.1 (see Resources) does not add new features, but it breaks XHTML into modules. Its value is reflected in two aspects. First, if we find that there is value in some modules but not in others, it can be easier to adopt a subset of it. For example, the Wireless Application Forum (WAP) has every reason to incorporate basic XHTML structures into its standards for delivering content to mobile phones, but it does not want to allow WAP documents to incorporate user interface features such as those used on mobile phones. The image mapping or editing module features are not very useful on the small screen.

Another benefit of a modular architecture for DTDs or schemas is that it can be easier to plug in new modules that are unique to a user's application. Combined with the ability to pick and choose existing modules, this capability brings benefits to the publishing industry: the PRISM standards group dedicated to publishing industry metadata selected a subset of XHTML 1.1 and then added some with industry-specific vocabulary new module to make it easier to track content through publishing workflows. (See Resources for more information about PRISM.)

You can compare developing XHTML 1.1 to cleaning out your basement: you probably won't have to throw away as much stuff, and by organizing it better, you'll be able to use it more easily Existing items can even free up space to build a workbench on which to make something new.

XHTML 1.1 has been a standard (or, in W3C parlance, a recommendation) since May 2001. The most recent development on XHTML 2.0 was the release of a new working draft in July 2006. Although it will have several stages to come to its final form, the availability of the RELAX NG schema (see Resources for a link) enables us to create and use XHTML 2 documents now so that we can quickly transition to the specification when it becomes a recommendation. to XHTML. A simple XSLT stylesheet will convert these files to XHTML 1 for display by the browser, or you can use a CSS stylesheet now included with the XHTML 2 Working Draft (see Resources) to display it in a browser (for now, Firefox should work better).

XHTML 2: What's new?

XHTML 2 retains the functionality of XHTML 1 to clean up existing syntax to make it more concise, while also adding some new features. It adds support for XForms, the more complete successor to forms that have been used in HTML for more than a decade. XHTML 2 also includes XML Events, which allow us to identify events triggered by certain user interface operations, thereby reducing the need to write scripts in JavaScript or ASP. These features will be interesting, especially once major browsers support them, but other features will be more interesting to publishers even before browsers support XHTML:

A richer, more reusable structure

Better device independence, easier access, and better semantics

Easier to add metadata

#p#

Richer Structure

Many publishers who need to store content in XML know that it is better to use an existing standard schema (by which I mean W3C Schema, RELAX NG Schema, or DTD) than to create one from scratch. They look at DocBook and find it too complex, they look at HTML or XHTML 1 and find it too simple. For many publishers, XHTML 2 is a good balance between the richness of DocBook and the simplicity of XHTML 1. This balance makes it an excellent format for storing content, regardless of whether the content needs to be converted into other formats for delivery in a variety of media.

Listing 1 contains a sample XHTML 1 file and shows its structure in indented format.

Listing 1. Structure of XHTML 1 file

My Web Page

Here is my Web page.

Section 1 of my Web page

Here is section 1 my Web page.

Section 1.1 of my Web page

Here is a subsection of my Web page.

Section 2 of my Web page

Here is section 2 of my Web page.

We can see inside the body element and There isn't much indentation, this is because there isn't much structure in the element. The tree representation of this document would show a body element with many child elements and no grandchild elements, and the paragraph "Here is a subsection of my Web page" would be shown as a sibling element of the main h1 heading "My Web Page". There is only one place in the markup that indicates that this paragraph is part of a subparagraph: the heading closest to it, h3, is a larger number than the preceding heading. The container element does not combine any header that serves as a heading with its content, unless the body element encapsulates the h1 header with the rest of the displayable content of the web page. We could use a p element to encapsulate each header/content combination, but the p element, like the span element, is a fairly general grouping element. It can be used for many purposes, such as indicating that some specific paragraphs form a menu or a sidebar or another visual presentation element in a Web page, so we cannot assume that it represents a structural unit of the indicated content.

The new section and h elements in XHTML 2 combine to allow us to create a richer structure that makes content easier to reuse. Listing 2 demonstrates the XHTML 2 body element equivalent to the body element in Listing 1.

Listing 2. XHTML 2 body element

Here is a subsection of my Web page.

Here is section 2 of my Web page.

In this version of the code, "Here is a subsection" paragraph is the great-grandchild of the first section element, and the "My Web Page" h element within this section element displays its main title—just as it should!

One of the advantages of this rich structure (and a key reason why XHTML 2 is better suited than XHTML 1 to serve as the central format for single-source publishing systems) is that it is easier to stream. If you need to process a large amount of input and cannot load it into memory before processing—for example, if you are preparing content for a CD-ROM—it will be easier for the processor to work out where each sectiong element ends in the XHTML 2 document . For example, let's say we want to call up all titles that contain the word "Beagle." Finding these headings is easy enough, but deciding where a section ends in XHTML 1 is not that difficult. Whether processing this XHTML uses a stream-based interface, Xquery, or XSLT, clearly defining where a section ends can make extraction much simpler.

Now, imagine that you extract these sections because you will be adding them to a new release about beagle, and each section you extract has an h3 element as its header. Numbered XHTML 1 headers, such as h3, are still legal in XHTML 2, but what if a new release will use these elements as the main section, or subsection, of a special section? You need to go back and change the h3 element to an h2 element or an h4 element, or whatever element recognizes its role in the new context. If they are XHTML 2 h elements in the original document, their role level is indicated by the number of each section ancestor element (for example, the section 1.1 h element in Listing 2 has three section header ancestor elements, and "My Web Page" h element), you can insert them into a new, unmodified document, with their roles indicated by the nested arrangement of the new document's section elements. CSS, XSLT, and other XML processing tools and standards all provide a way to handle elements with the same name based on nesting levels, so we don't miss the number that is part of the XHTML 1 header. When we consider the number of (X)HTML documents that have h2 and h3 elements but no h1 element, or h1 and h3 elements but no h2 element, it becomes clear that too many people are not using them to indicate the appropriate hierarchy.

In XHTML 2, there can be more structures within the p element. I'd like to introduce some example code within a statement, like this one:

print "Hello? World?";

If I want to continue the statement after the example code, XHTML 1 forces me to split the statement into two parts are placed in two different p elements, but semantically they are in the same statement. XHTML 2 lets us place sample code, unordered and numbered lists, and many other block elements inside a p element, allowing our markup to more accurately reflect the structure of the document.

To take a small step from presentation markup to structural markup, rename the hr element to separator. The HTML Working Group found that its original name, which stood for horizontal rule, often fell into the gray area between structural and presentational markup. They received some vertical rule requests from users in Asian languages, and they saw that many of the horizontal separators were not really rules (Steven Pemberton, chair of the HTML Working Group, made a statement in which he pointed out that in James Joyce's Ulysses Several different variations; see Resources for a link to this statement). This allowed them to rename the hr element to more accurately return the name it was used for and allowed for more flexibility in statements.

#p# Better device independence, easier access, and better semantics

These three goals actually overlap with each other. Text-to-speech translators that read out the content of a Web page still make sense for Web pages that do not need to be delivered across a platform and that are easily understood by users with reduced vision. It is mentioned in the XHTML 2 Working Draft:

Various new devices appear on the network, such as phones, PDAs, writing pads, TVs, etc., which means there needs to be a design that allows us to create once Then render it differently on different devices, rather than authoring a new version of the document for each type of device.

The publisher does not need to consider its value in the future. Device independence made many of them applicable to SGML before the invention of XML, because it allowed these devices to publish the same content in print, on a Web page, and on a CD-ROM, as long as there was enough stored in the edited version of the content structural and semantic information, allowing automatic routines to convert it into the respective format. I remember the snickers that filled my old boss's office eleven years ago when our competitors were going to store edited versions of content as HTML; using XHTML 2 wasn't such a crazy idea anymore.

If the existing semantics of XHTML 2 elements are not enough for you, the new role attribute (which can be added to any element) can tell you more about the purpose of the element. The XHTML 2 specification specifies nine possible values for this attribute: banner, note, contentinfo, search, definition, secondary, main, seealso, and navigation. Role values, such as banner and navigation, are obviously more presentation-oriented, but for values like definition and note, the semantics are more practical in a publishing environment where content is prepared for multimedia. You can even construct your own role values, as long as they are in their own namespace. Easier to add metadata

The W3C RDF standard lets us assign metadata to any content that can be identified using a URL. The standard RDF/XML syntax for this operation appeared in 1999, and its complexity and difficulty scared many people away. By using existing HTML attributes and adding some new ones, XHTML 2 lets us use new, simpler RDFa syntax to add metadata about documents and document components (which can be identified using an about attribute). In some of the examples in Listing 3, the span element stores the additional information needed to embed a subject-verb-object triplet (it might be easier as an object ID-attribute name-attribute value triplet) to represent RDF metadata.

Listing 3. Encoding metadata using span elements

< ;span property="fb:workflowStage" content="3a"/>

Carrion, My Wayward Son

The dream of Semantic Web is mainly to allow Web page data to be published as content for people to read, and as data for programmers to read, starting from the database, such as the dc:title example demonstrated in Listing 3 . The fb:workflowStage example demonstrates another advantage of RDFa: we can actually add arbitrary metadata to an XHTML 2 document specifically for your own store, which makes the document easier to track and reuse.

Start using XHTML 2 now

We still have to wait a while before we can use the newer user interface features in XHTML 2m, such as XML Events, but we can experiment with the new structural features in XHTML 2 now. As an unfinished specification, XHTML 2 is still a work in progress, but progress is slow. The schema and CSS stylesheet are currently available and we can try it out and consider what benefits it might bring to our operations. In fact, I wrote this article using it, Driving context-sensitive XML editing in XHTML 2's RELAX NG mode using Emacs in nXML mode (see Related topics). Before I submitted this article, I used a simple XSLT stylesheet to convert it into a format that conforms to the developerWorks DTD. By the time XHTML 2 becomes a standard recommendation, I plan to have it running at full speed.

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

Video Face Swap

Swap faces in any video effortlessly with our completely free AI face swap tool!

Hot Article

Hot Tools

Notepad++7.3.1

Easy-to-use and free code editor

SublimeText3 Chinese version

Chinese version, very easy to use

Zend Studio 13.0.1

Powerful PHP integrated development environment

Dreamweaver CS6

Visual web development tools

SublimeText3 Mac version

God-level code editing software (SublimeText3)

Hot Topics

1653

1653

14

14

1413

1413

52

52

1304

1304

25

25

1251

1251

29

29

1224

1224

24

24

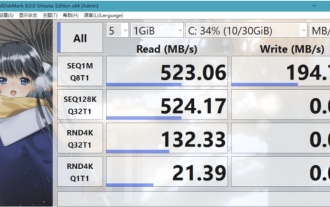

What software is crystaldiskmark? -How to use crystaldiskmark?

Mar 18, 2024 pm 02:58 PM

What software is crystaldiskmark? -How to use crystaldiskmark?

Mar 18, 2024 pm 02:58 PM

CrystalDiskMark is a small HDD benchmark tool for hard drives that quickly measures sequential and random read/write speeds. Next, let the editor introduce CrystalDiskMark to you and how to use crystaldiskmark~ 1. Introduction to CrystalDiskMark CrystalDiskMark is a widely used disk performance testing tool used to evaluate the read and write speed and performance of mechanical hard drives and solid-state drives (SSD). Random I/O performance. It is a free Windows application and provides a user-friendly interface and various test modes to evaluate different aspects of hard drive performance and is widely used in hardware reviews

How to download foobar2000? -How to use foobar2000

Mar 18, 2024 am 10:58 AM

How to download foobar2000? -How to use foobar2000

Mar 18, 2024 am 10:58 AM

foobar2000 is a software that can listen to music resources at any time. It brings you all kinds of music with lossless sound quality. The enhanced version of the music player allows you to get a more comprehensive and comfortable music experience. Its design concept is to play the advanced audio on the computer The device is transplanted to mobile phones to provide a more convenient and efficient music playback experience. The interface design is simple, clear and easy to use. It adopts a minimalist design style without too many decorations and cumbersome operations to get started quickly. It also supports a variety of skins and Theme, personalize settings according to your own preferences, and create an exclusive music player that supports the playback of multiple audio formats. It also supports the audio gain function to adjust the volume according to your own hearing conditions to avoid hearing damage caused by excessive volume. Next, let me help you

BTCC tutorial: How to bind and use MetaMask wallet on BTCC exchange?

Apr 26, 2024 am 09:40 AM

BTCC tutorial: How to bind and use MetaMask wallet on BTCC exchange?

Apr 26, 2024 am 09:40 AM

MetaMask (also called Little Fox Wallet in Chinese) is a free and well-received encryption wallet software. Currently, BTCC supports binding to the MetaMask wallet. After binding, you can use the MetaMask wallet to quickly log in, store value, buy coins, etc., and you can also get 20 USDT trial bonus for the first time binding. In the BTCCMetaMask wallet tutorial, we will introduce in detail how to register and use MetaMask, and how to bind and use the Little Fox wallet in BTCC. What is MetaMask wallet? With over 30 million users, MetaMask Little Fox Wallet is one of the most popular cryptocurrency wallets today. It is free to use and can be installed on the network as an extension

How to use NetEase Mailbox Master

Mar 27, 2024 pm 05:32 PM

How to use NetEase Mailbox Master

Mar 27, 2024 pm 05:32 PM

NetEase Mailbox, as an email address widely used by Chinese netizens, has always won the trust of users with its stable and efficient services. NetEase Mailbox Master is an email software specially created for mobile phone users. It greatly simplifies the process of sending and receiving emails and makes our email processing more convenient. So how to use NetEase Mailbox Master, and what specific functions it has. Below, the editor of this site will give you a detailed introduction, hoping to help you! First, you can search and download the NetEase Mailbox Master app in the mobile app store. Search for "NetEase Mailbox Master" in App Store or Baidu Mobile Assistant, and then follow the prompts to install it. After the download and installation is completed, we open the NetEase email account and log in. The login interface is as shown below

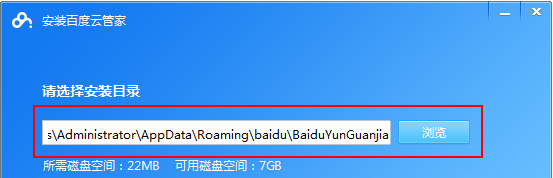

How to use Baidu Netdisk app

Mar 27, 2024 pm 06:46 PM

How to use Baidu Netdisk app

Mar 27, 2024 pm 06:46 PM

Cloud storage has become an indispensable part of our daily life and work nowadays. As one of the leading cloud storage services in China, Baidu Netdisk has won the favor of a large number of users with its powerful storage functions, efficient transmission speed and convenient operation experience. And whether you want to back up important files, share information, watch videos online, or listen to music, Baidu Cloud Disk can meet your needs. However, many users may not understand the specific use method of Baidu Netdisk app, so this tutorial will introduce in detail how to use Baidu Netdisk app. Users who are still confused can follow this article to learn more. ! How to use Baidu Cloud Network Disk: 1. Installation First, when downloading and installing Baidu Cloud software, please select the custom installation option.

Teach you how to use the new advanced features of iOS 17.4 'Stolen Device Protection'

Mar 10, 2024 pm 04:34 PM

Teach you how to use the new advanced features of iOS 17.4 'Stolen Device Protection'

Mar 10, 2024 pm 04:34 PM

Apple rolled out the iOS 17.4 update on Tuesday, bringing a slew of new features and fixes to iPhones. The update includes new emojis, and EU users will also be able to download them from other app stores. In addition, the update also strengthens the control of iPhone security and introduces more "Stolen Device Protection" setting options to provide users with more choices and protection. "iOS17.3 introduces the "Stolen Device Protection" function for the first time, adding extra security to users' sensitive information. When the user is away from home and other familiar places, this function requires the user to enter biometric information for the first time, and after one hour You must enter information again to access and change certain data, such as changing your Apple ID password or turning off stolen device protection.

What is chirp down? -How to use chirp down

Mar 18, 2024 am 11:46 AM

What is chirp down? -How to use chirp down

Mar 18, 2024 am 11:46 AM

Chirp Down can also be called JJDown. This is a video download tool specially created for Bilibili. However, many friends do not understand this software. Today, let the editor explain to you what Chirp Down is? How to use chirp down. 1. The origin of Chirpdown Chirpdown originated in 2014. It is a very old video downloading software. The interface adopts Win10 tile style, which is simple, beautiful and easy to operate. Chirna is the poster girl of Chirpdown, and the artist is あさひクロイ. Jijidown has always been committed to providing users with the best download experience, constantly updating and optimizing the software, solving various problems and bugs, and adding new functions and features. The function of Chirp Down Chirp Down is

Word document is blank when opening on Windows 11/10

Mar 11, 2024 am 09:34 AM

Word document is blank when opening on Windows 11/10

Mar 11, 2024 am 09:34 AM

When you encounter a blank page issue when opening a Word document on a Windows 11/10 computer, you may need to perform repairs to resolve the situation. There are various sources of this problem, one of the most common being a corrupted document itself. Furthermore, corruption of Office files may also lead to similar situations. Therefore, the fixes provided in this article may be helpful to you. You can try to use some tools to repair the damaged Word document, or try to convert the document to another format and reopen it. In addition, checking whether the Office software in the system needs to be updated is also a way to solve this problem. By following these simple steps, you may be able to fix Word document blank when opening Word document on Win