Web Front-end

Web Front-end

JS Tutorial

JS Tutorial

Mastering Data Validation in NestJS: A Complete Guide with Class-Validator and Class-Transformer

Mastering Data Validation in NestJS: A Complete Guide with Class-Validator and Class-Transformer

Mastering Data Validation in NestJS: A Complete Guide with Class-Validator and Class-Transformer

Introduction

In the fast-paced world of development, data integrity and reliability are paramount. Robust data validation and efficient handling of user data can make the difference between a smooth experience and an inconsistent application state.

George Fuechsel’s quote below summarizes what this article is about.

“Garbage in, garbage out.” — George Fuechsel

In this article, we will dive into data validation in NestJS. We will explore some complex use cases of class-validator and class-transformer to ensure data are valid and properly formatted. Along the way, we will discuss best practices, some advanced techniques, and common pitfalls to take your skills to the next level. My motive is to equip you to build more resilient and error-proof applications with NestJS.

Whiles we go through this journey together, keep in mind that we should never trust any inputs submitted by a user or client external to the application, regardless of whether it is part of a larger service(micro-service).

Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Data Transfer Object (DTO). What is it?

- Initial Configuration: Setting Up Your NestJS Project

- Creating User DTOs

- Adding Class Validators to Fields

- Validating Nested Objects

- Using Transform() and Type() from Class-transformer

- Conditional Validation

- Handling Validation Errors

- Understanding Pipes

- Setting Up a Global Validation Pipe

- Formatting Validation Errors

- Creating Custom Validators

- Custom Password Validator

- Asynchronous Custom Validator With Custom Validation Options

- Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

- Conclusion

- Additional Resources

Data Transfer Object (DTO). What is it?

DTO is a pattern we can leverage to encapsulate data and transfer it to different layers of the application. They are useful for managing the data that flows in(request) and out(response) of the app.

Immutable DTOs

As we have already established, the main idea for using DTOs is to transfer data and as such, the data should not be changed after they have been created. In general, DTOs are designed to be immutable, meaning that once they are created their properties can not be modified. Some benefit that comes with this include but not limited to:

- Predictable behavior: The confidence that its data remains unchanged.

- Consistency: Once it is created, its state remains unchanged throughout its lifecycle until it’s garbage collected.

JavaScript does not have a built-in type for creating immutable types like we have record types in Java and C#. We can achieve similar behavior by making our fields readonly.

Initial Configuration: Setting Up Your NestJS Project

We will start with a mini user management project, which will include basic CRUD operations to manage users. If you’d like to explore the full source code, you can click here to access the project on GitHub.

Install NestJS CLI

$ npm i -g @nestjs/cli $ nest new user-mgt

Install class-validator and class-transformer

npm i --save class-validator class-transformer

Generate the user module

$ nest g resource users ? What transport layer do you use? REST API ? Would you like to generate CRUD entry points? No

Create an empty DTO and entities folder. After everything, you should have this structure.

Creating User DTOs

Let’s begin by creating the necessary DTOs. This tutorial will focus on only two actions, creating and updating a user. Create two files in the DTO folder

user-create.dto.ts

export class UserCreateDto {

public readonly name: string;

public readonly email: string;

public readonly password: string;

public readonly age: number;

public readonly dateOfBirth: Date;

public readonly photos: string[];

}

user-update.dto.ts

import { PartialType } from '@nestjs/mapped-types';

import { UserCreateDto } from './user-create.dto';

export class UserUpdateDto extends PartialType(UserCreateDto) {}

UserUpdateDto extends UserCreateDto to inherit all properties, the PartialType ensures that all fields are optional allowing for partial update. This saves us time so we don’t have to repeat it.

Adding Class Validators to Fields

Let’s break down how to add validation to the fields. Class-validator provides us with a lot of already-made validation decorators to which we can apply these rules to our DTOs. For now, we will use a few to validate UserCreateDto. click here for the full list.

import {

IsString,

IsEmail,

IsInt,

Min,

Max,

Length,

IsDate,

IsArray,

ArrayNotEmpty,

ValidateNested,

IsUrl,

} from 'class-validator';

import { Transform, Type } from 'class-transformer';

export class UserCreateDto {

@IsString()

@Length(2, 30, { message: 'Name must be between 2 and 30 characters' })

@Transform(({ value }) => value.trim())

public readonly name: string;

@IsEmail({}, { message: 'Invalid email address' })

public readonly email: string;

@IsString()

@Length(8, 50, { message: 'Password must be between 8 and 50 characters' })

public readonly password: string;

@IsInt()

@Min(18, { message: 'Age must be at least 18' })

@Max(100, { message: 'Age must not exceed 100' })

public readonly age: number;

@IsDate({ message: 'Invalid date format' })

@Type(() => Date)

public readonly dateOfBirth: Date;

@IsArray()

@ValidateNested()

@ArrayNotEmpty({ message: 'Photos array should not be empty' })

@IsString({ each: true, message: 'Each photo URL must be a string' })

@IsUrl({}, { each: true, message: 'Each photo must be a valid URL' })

public readonly photos: string[];

}

Our simple class has grown in size, we have annotated the fields with decorators from Class-Validator. These decorators apply validation rules to the fields. You may have questions about the decorators if you are new to this. For example, what do they mean? Let’s break down some of the basic validators we have used.

- IsString() → This decorator ensures that a value is a string.

- Length(min, max) → This ensures that the string has a link within the specified range.

- IsInt() → This decorator checks if the value is an integer.

- Min() and Max() → This ensures that a numeric value falls between the range

- IsDate() → This ensures that the value is a valid date

- IsArray() → Validates that the value is an array

- IsUrl() → Validate the value is a valid URL

- Transform() → Change the data into a different format

Decorator Parameters

The UserCreateDto fields validator contains additional properties passed into it. These allow you to:

- Customize validation rules

- Provide values

- Set validation options

- Provide messages when the validation fails etc.

Validating Nested Objects

Unlike normal fields validating nested objects requires a bit of extra processing, class-transformer together with class-validator allows you to validate nested objects.

We did a little bit of nested validation in UserCreateDto when we validated the photos field.

@IsArray()

@IsUrl({}, { each: true, message: 'Each photo must be a valid URL' })

public readonly photos: string[];

Photos are an array of strings. To validate the nested strings, we added ValidateNested() and { each: true } to ensure that, each link is a valid URL.

Let’s update photos a some-what complex structure. create a new file in DTO folder and name it user-photo.dto.ts

import { IsString, IsInt, Min, Max, IsUrl, Length } from 'class-validator';

export class UserPhotoDto {

@IsString()

@Length(2, 100, { message: 'Name must be between 2 and 100 characters' })

public readonly name: string;

@IsInt()

@Min(1, { message: 'Size must be at least 1 byte' })

@Max(5_000_000, { message: 'Size must not exceed 5MB' })

public readonly size: number;

@IsUrl(

{ protocols: ['http', 'https'], require_protocol: true },

{ message: 'Invalid URL format' },

)

public readonly url: string;

}

Now let’s update the photos section of UserCreateDto

export class UserCreateDto {

// Other fields

@IsArray()

@ArrayNotEmpty({ message: 'Photos array should not be empty' })

@ValidateNested({ each: true })

@Type(() => UserPhotoDto)

public readonly photos: UserPhotoDto[];

}

The ValidateNested() decorator ensures that each element in the array is a valid photo object. The most important thing to be aware of when it comes to nested validation is that the nested object must be an instance of a class else ValidateNested() won’t know the target class for validation. This is where class-transformer comes in.

Using Transform() and Type() from Class-transformer

Class-transformer provides us with the @Type() decorator. Since Typescript doesn’t have good reflection capabilities yet, we use @Type(() => UserPhotoDto) to give an instance of the class.

We can also utilize the Type() decorator for basic data transformation in our DTO. The dateOfBirth field in UserCreateDto is transformed into a date object using @Type(() => Date).

For complex DTO fields transformation, the Tranform() decorator handles this perfectly. It allows you to access both the field value and the entire object being validated. Whether you’re converting data types, formatting strings, or applying custom logic, @Transform() gives you the control to return the exact version of the value that your application needs.

@Transform(({ value, obj }) => {

// perform additional transformation

return value;

})

Conditional Validation

Most often, some fields need to be validated based on some business rules, we can use the ValidateIf() decorator, which allows you to apply validation to a field only if some condition is true. This is very useful if a field depends on other fields like multi-step forms.

Let’s update the UserPhotoDto to include an optional description field, which should only be validated if it is provided. If the description is present, it should be a string with a length between 10 and 200 characters.

export class UserPhotoDto {

// Other fields

@ValidateIf((o) => o.description !== undefined)

@IsString({ message: 'Description must be a string' })

@Length(10, 200, {

message: 'Description must be between 10 and 200 characters',

})

public readonly description?: string;

}

Handling Validation Errors

Before we dive into how NestJS handles validation errors, let’s first create simple handlers in the user.controller.ts. We need a basic route to handle user creation.

import { Body, Controller, Post } from '@nestjs/common';

import { UserCreateDto } from './dto/user-create.dto';

@Controller('users')

export class UsersController {

@Post()

createUser(@Body() userCreateDto: UserCreateDto) {

// delegating the creation to a service

return {

message: 'User created successfully!',

user: userCreateDto,

};

}

}

Trying this endpoint on Postman with no payload gives us a successful response.

NestJS has a good integration with class-validator for data validation. Still, why wasn’t our request validated? To tell NestJS that we want to validate UserCreateDto we have to supply a pipe to the Body() decorator.

Understanding Pipes

Pipes are flexible and powerful ways to transform and validate incoming data. Pipes are any class decorated with Injectable() and implement the PipeTransform interface. The usage of pipe we are interested is its ability to check that an incoming request meets a certain criteria or throw errors if otherwise.

The most common way to validate the UserCreateDto is to use the built-in ValidationPipe. This pipe validates rules in your DTO defined with class-validator

Now we pass a validation pipe to the Body() to validate the DTO

import { Body, Controller, Post, ValidationPipe } from '@nestjs/common';

import { UserCreateDto } from './dto/user-create.dto';

@Controller('users')

export class UsersController {

@Post()

createUser(@Body(new ValidationPipe()) userCreateDto: UserCreateDto) {

// delegating the creation to services

return {

message: 'User created successfully!',

user: userCreateDto,

};

}

}

With this small change, we get the errors below if we try to create a user with no payload.

Awesome right :)

Setting Up a Global Validation Pipe

To ensure that all requests are validated across the entire application. We have to set up a global validation pipe so that we don’t have to pass validation pipe to every Body() decorator.

Update main.ts

import { NestFactory } from '@nestjs/core';

import { AppModule } from './app.module';

import { ValidationPipe } from '@nestjs/common';

async function bootstrap() {

const app = await NestFactory.create(AppModule);

app.useGlobalPipes(

new ValidationPipe({

whitelist: true,

transform: true,

}),

);

await app.listen(3000);

}

bootstrap();

The built-in validation pipe uses class-transformer and class-validator, we can pass validations options to be used by these underlying packages. whitelist: true automatically strips any properties that are not defined in the DTO.transform: true automatically transforms the payload into the appropriate types defined in your DTO.

ValidationPipe({

whitelist: true,

transform: true,

}),

With this, we can remove the pipe we passed to createUser endpoint and it will still be validated. Passing it to parameters helps us fine-tune the validation we need for specific endpoints.

@Post()

createUser(@Body() userCreateDto: UserCreateDto) {

// ...

}

Formatting Validation Errors

The default validation errors format is not bad, we get to see all the errors for the validations that failed, Some frontend developers will scream at you though for mixing all the errors, I have been there?. Another reason to separate it is when you want to display errors under the fields that failed on the UI.

For nested objects, we also need to retrieve all the errors recursively for a smooth experience. We can achieve this by passing a custom exceptionFactory method to format the errors.

Update main.ts

import { NestFactory } from '@nestjs/core';

import { AppModule } from './app.module';

import {

BadRequestException,

ValidationError,

ValidationPipe,

} from '@nestjs/common';

async function bootstrap() {

const app = await NestFactory.create(AppModule);

app.useGlobalPipes(

new ValidationPipe({

transform: true,

whitelist: true,

exceptionFactory: (validationErrors: ValidationError[] = []) => {

const getPrettyClassValidatorErrors = (

validationErrors: ValidationError[],

parentProperty = '',

): Array<{ property: string; errors: string[] }> => {

const errors = [];

const getValidationErrorsRecursively = (

validationErrors: ValidationError[],

parentProperty = '',

) => {

for (const error of validationErrors) {

const propertyPath = parentProperty

? `${parentProperty}.${error.property}`

: error.property;

if (error.constraints) {

errors.push({

property: propertyPath,

errors: Object.values(error.constraints),

});

}

if (error.children?.length) {

getValidationErrorsRecursively(error.children, propertyPath);

}

}

};

getValidationErrorsRecursively(validationErrors, parentProperty);

return errors;

};

const errors = getPrettyClassValidatorErrors(validationErrors);

return new BadRequestException({

message: 'validation error',

errors: errors,

});

},

}),

);

await app.listen(3000);

}

bootstrap();

This looks way better. Hopefully, you don’t go through what I went through with the front-end developers to get here ?. Let’s go through what is happening.

We passed an anonymous function to exceptionFactory. The functions accept the array of validation errors. Diving into the validationError interface.

export interface ValidationError {

target?: Record<string, any>;

property: string;

value?: any;

constraints?: {

[type: string]: string;

};

children?: ValidationError[];

contexts?: {

[type: string]: any;

};

}

For example, if we apply IsEmail() on a field and the provided value is not valid. A validation error is created. We also want to know the property where the error occurred. We need to keep in mind that, we can have nested objects for example the photos in UserCreateDto and therefore we can have a parent property let’s say, photos where the error is with the url in the UserPhotoDto.

We first declare an inner function, that takes the errors and sets the parent property to an empty string since it is the root field.

const getValidationErrorsRecursively = (

validationErrors: ValidationError[],

parentProperty = '',

) => {

};

We then loop through the errors and get the property. For nested objects, I prefer to show the fields as photos.0.url. Where 0 is the index of the invalid photo in the array.

The error messages are stored in the constraints field as it’s in the validationError interface. We retrieve these errors and store them under a specific field.

if (error.constraints) {

errors.push({

property: propertyPath,

errors: Object.values(error.constraints),

});

}

For nested objects, the children property of a validation error contains an array of validationError for the nested objects. We can easily get the errors by recursively calling our function and passing the parent property.

if (error.children?.length) {

getValidationErrorsRecursively(error.children, propertyPath);

}

Creating Custom Validators

While Class-validator provides a comprehensive set of built-in validators, there are times when your requirements exceed the standard validation rules or the standard validation doesn’t fit what you want to do. Custom validators are useful when you need to enforce rules that aren’t covered by the standard validators. Examples:

- We can create a custom validator to enforce a specific rule on what a valid password should be.

- We can create another to ensure that the username is unique.

To create a custom validator, we have to define a new class that implements the ValidatorConstraintInterface from class-validator. This requires us to implement two methods:

- validate → Contains your validation logic and must return a boolean

- defaultMessage → Optional default message to return when the validation fails.

Custom Password Validator

Create a new folder in users module named validators. Create two files, is-valid-password.validator.ts and is-username-unique.validator.ts. It should look like this.

A valid password in our use case is very simple. it should contains

- At least one uppercase letter.

- At least one lowercase letter.

- At least one symbol.

- At least one number.

- Password length should be more than 5 characters and less than 20 characters.

Update is-valid-password.validator.ts

import {

ValidatorConstraint,

ValidatorConstraintInterface,

ValidationArguments,

} from 'class-validator';

@ValidatorConstraint({ name: 'IsStrongPassword', async: false })

export class IsValidPasswordConstraint implements ValidatorConstraintInterface {

validate(password: string, args: ValidationArguments) {

return (

typeof password === 'string' &&

password.length > 5 &&

password.length <= 20 &&

/[A-Z]/.test(password) &&

/[a-z]/.test(password) &&

/[0–9]/.test(password) &&

/[!@#$%^&*(),.?":{}|<>]/.test(password)

);

}

defaultMessage(args: ValidationArguments) {

return 'Password must be between 6 and 20 characters long and include at least one uppercase letter, one lowercase letter, one number, and one special character';

}

}

IsValidPasswordContraint is a custom validator because it is decorated with ValidatorConstraint(), we provide our custom validation rules in the validate method. If the validate function returns false, the error message in the defaultMessage will be returned. Providing these methods implements the ValidatorContraintInterface. To use isValidPasswordContraint, update the password field in UserCreateDto. For ValidatorConstraint({ name: ‘IsStrongPassword’, async: false }), we provided the constraint name that will be used to retrieve the error and also, since all actions in the validate are synchronous, we set async to false.

import { Validate } from 'class-validator';

export class UserCreateDto {

// other fields

@Validate(IsValidPasswordConstraint)

public readonly password: string;

}

Now, if we try again with an invalid password, we get this result indicating our custom validator is working.

We can go further and create a decorator for the validator so that we can decorate the password field without using the Validate.

Update is-valid-password.validator.ts

import {

ValidatorConstraint,

ValidatorConstraintInterface,

ValidationArguments,

registerDecorator,

ValidatorOptions,

} from 'class-validator';

@ValidatorConstraint({ name: 'IsStrongPassword', async: false })

class IsValidPasswordConstraint implements ValidatorConstraintInterface {

// removing the implementation so that we focus on IsPasswordValid function

}

export function IsValidPassword(validationOptions?: ValidatorOptions) {

return function (object: NonNullable<unknown>, propertyName: string) {

registerDecorator({

target: object.constructor,

propertyName: propertyName,

options: validationOptions,

constraints: [],

validator: IsValidPasswordConstraint,

});

};

}

Creating custom decorators makes working with validators a breeze, NestJs gives us registerDecorator to create our own. we provide it with the validator which is the IsValidPasswordContraint we created. We can use it like this

export class UserCreateDto {

// other fields

@IsValidPassword()

public readonly password: string;

}

Asynchronous Custom Validator With Custom Validation Options

It is common to encounter scenarios where you need to validate against external systems. Let’s assume that the username in UserCreateDto is unique across the various servers.

Update is-unique-username.validator.ts

import {

ValidatorConstraint,

ValidatorConstraintInterface,

ValidationArguments,

registerDecorator,

ValidationOptions,

} from 'class-validator';

interface IsUsernameUniqueOptions {

server: string;

message?: string;

}

@ValidatorConstraint({ name: 'IsUsernameUnique', async: true })

export class IsUsernameUniqueConstraint

implements ValidatorConstraintInterface

{

async validate(username: string, args: ValidationArguments) {

const options = args.constraints[0] as IsUsernameUniqueOptions;

const server = options.server;

// server check, let assume username exist

return !(await this.checkUsernameOnServer(username, server));

}

defaultMessage(args: ValidationArguments) {

const options = args?.constraints[0] as IsUsernameUniqueOptions;

return options?.message || 'Username is already taken';

}

async checkUsernameOnServer(username: string, server: string) {

return true;

}

}

export function IsUsernameUnique( options: IsUsernameUniqueOptions,

validationOptions?: ValidationOptions,) {

return function (object: object, propertyName: string) {

registerDecorator({

target: object.constructor,

propertyName: propertyName,

options: validationOptions,

constraints: [options],

validator: IsUsernameUniqueConstraint,

});

};

}

Usage

export class UserCreateDto {

@IsString()

@Length(2, 30, { message: 'Name must be between 2 and 30 characters' })

@Transform(({ value }) => value.trim())

@IsUsernameUnique({ server: 'east-1', message: 'Name already exists' })

public readonly name: string;

// other fields

}

We created a simple interface to show the possible options we can pass to the decorator. These options are constraints that will be used by IsUsernameUniqueConstraint, we can get them through the validation arguments . const options = args.constraints[0] as IsUsernameUniqueOptions;

Logging options give us { server: ‘east-1’, message: ‘Name already exists’ }, We then called the required service and passed the server name and username to validate the uniqueness of the name.

Also, async is set to true to allow asynchronous operations inside the validate function; ValidatorConstraint({ name: ‘IsUsernameUnique’, async: true }).

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

It is necessary to be aware of common pitfalls to ensure robust and maintainable code.

- Avoid direct use of entities. One common mistake is using entities directly. Entities are typically used for database interactions and may contain fields or relationships that shouldn’t be exposed or validated on incoming requests.

- Test Custom Validators Extensively. Validation logic is a critical part of your application’s security and data integrity. Ensure they are well-tested.

- Be Explicit with Error Messages. Provide error messages that are informative and user-friendly. It should communicate what the user should do to correct it.

- Leverage Built-in and Custom Validators Together. Our IsUniqueUsername validator still uses IsString() on the name field. We don’t have to reinvent everything if it is already available.

Conclusion

There is so much to add like validation groups, using service containers, etc, but this article is getting way longer than I anticipated ?. As you continue developing with NestJS, I encourage you to explore more complex use cases and scenarios and share your experiences to keep the learning journey going.

Data validation is crucial in ensuring data integrity within any application and the principles covered here will serve as a strong foundation for further growth and mastery in building secure and efficient applications.

This is my very first article, and I’m eager to hear your thoughts! ? Please feel free to leave any feedback in the comments.

If you’d like to connect and stay updated on future content, you can find me on LinkedIn

Happy Coding !!!

추가 리소스

- https://github.com/typestack/class-validator?tab=readme-ov-file#class-validator

- https://github.com/typestack/class-transformer?tab=readme-ov-file#what-is-class-transformer

- https://docs.nestjs.com/pipes

- https://docs.nestjs.com/techniques/validation

The above is the detailed content of Mastering Data Validation in NestJS: A Complete Guide with Class-Validator and Class-Transformer. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

AI Hentai Generator

Generate AI Hentai for free.

Hot Article

Hot Tools

Notepad++7.3.1

Easy-to-use and free code editor

SublimeText3 Chinese version

Chinese version, very easy to use

Zend Studio 13.0.1

Powerful PHP integrated development environment

Dreamweaver CS6

Visual web development tools

SublimeText3 Mac version

God-level code editing software (SublimeText3)

Hot Topics

1359

1359

52

52

Replace String Characters in JavaScript

Mar 11, 2025 am 12:07 AM

Replace String Characters in JavaScript

Mar 11, 2025 am 12:07 AM

Detailed explanation of JavaScript string replacement method and FAQ This article will explore two ways to replace string characters in JavaScript: internal JavaScript code and internal HTML for web pages. Replace string inside JavaScript code The most direct way is to use the replace() method: str = str.replace("find","replace"); This method replaces only the first match. To replace all matches, use a regular expression and add the global flag g: str = str.replace(/fi

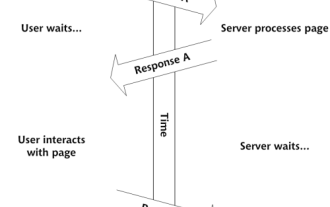

Build Your Own AJAX Web Applications

Mar 09, 2025 am 12:11 AM

Build Your Own AJAX Web Applications

Mar 09, 2025 am 12:11 AM

So here you are, ready to learn all about this thing called AJAX. But, what exactly is it? The term AJAX refers to a loose grouping of technologies that are used to create dynamic, interactive web content. The term AJAX, originally coined by Jesse J

How do I create and publish my own JavaScript libraries?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:12 PM

How do I create and publish my own JavaScript libraries?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:12 PM

Article discusses creating, publishing, and maintaining JavaScript libraries, focusing on planning, development, testing, documentation, and promotion strategies.

How do I optimize JavaScript code for performance in the browser?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:14 PM

How do I optimize JavaScript code for performance in the browser?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:14 PM

The article discusses strategies for optimizing JavaScript performance in browsers, focusing on reducing execution time and minimizing impact on page load speed.

How do I debug JavaScript code effectively using browser developer tools?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:16 PM

How do I debug JavaScript code effectively using browser developer tools?

Mar 18, 2025 pm 03:16 PM

The article discusses effective JavaScript debugging using browser developer tools, focusing on setting breakpoints, using the console, and analyzing performance.

jQuery Matrix Effects

Mar 10, 2025 am 12:52 AM

jQuery Matrix Effects

Mar 10, 2025 am 12:52 AM

Bring matrix movie effects to your page! This is a cool jQuery plugin based on the famous movie "The Matrix". The plugin simulates the classic green character effects in the movie, and just select a picture and the plugin will convert it into a matrix-style picture filled with numeric characters. Come and try it, it's very interesting! How it works The plugin loads the image onto the canvas and reads the pixel and color values: data = ctx.getImageData(x, y, settings.grainSize, settings.grainSize).data The plugin cleverly reads the rectangular area of the picture and uses jQuery to calculate the average color of each area. Then, use

How to Build a Simple jQuery Slider

Mar 11, 2025 am 12:19 AM

How to Build a Simple jQuery Slider

Mar 11, 2025 am 12:19 AM

This article will guide you to create a simple picture carousel using the jQuery library. We will use the bxSlider library, which is built on jQuery and provides many configuration options to set up the carousel. Nowadays, picture carousel has become a must-have feature on the website - one picture is better than a thousand words! After deciding to use the picture carousel, the next question is how to create it. First, you need to collect high-quality, high-resolution pictures. Next, you need to create a picture carousel using HTML and some JavaScript code. There are many libraries on the web that can help you create carousels in different ways. We will use the open source bxSlider library. The bxSlider library supports responsive design, so the carousel built with this library can be adapted to any

How to Upload and Download CSV Files With Angular

Mar 10, 2025 am 01:01 AM

How to Upload and Download CSV Files With Angular

Mar 10, 2025 am 01:01 AM

Data sets are extremely essential in building API models and various business processes. This is why importing and exporting CSV is an often-needed functionality.In this tutorial, you will learn how to download and import a CSV file within an Angular