Is this link safe? How to check safely—without clicking on it

Phishing and malvertising are among the biggest dangers on the internet. Both of these rely on deceptive links that can lead to peril.

But how can you recognize a malicious or dangerous link? Is there any way to be sure that a site will be safe before you actually go there? Whatever you do, don’t just blindly click that link or visit that site!

It’s important to know how to detect dangerous links in emails, messages, or on the web. In this article, we will explain what to look for, and how to determine whether a link is real or potentially hazardous. Read this guide to learn the secrets of link safety.

What are phishing attacks, and why are they effective?

In phishing attacks, threat actors try to get you to enter your username and password on a fake website so they can take over your accounts. They may try to access your bank accounts, social media, or even your e-mail—which arguably might be the most important of all. If hackers get access to your email account, they can change all your passwords via “forgot password” mechanisms. And if they succeed, they can lock you out of your own accounts permanently.

In some cases, cybercriminals don’t necessarily want to make you think you’re logging into a high-value account. Since so many people reuse the same credentials (username or e-mail address and password), getting that combination by tricking you into logging into an unimportant website could give hackers access to all of your accounts. This is why you should always use a password manager, and never use the same credentials on more than one website.

What is malvertising? Can I trust Google search results?

And that’s just phishing attacks. Meanwhile, one of the biggest threats to your security today is malvertising, or fake ads. Advertisement links at the top of search results pages may not look like ads—or, even if they do, might look like legitimate ads for a company.

But Google and others are often bad at vetting these ads, so you may end up clicking on a link that goes to an attacker’s site. We’ve written about many specific instances of malvertising attacks over the past year; very often they lead to Mac or Windows malware infections. Fake ads can, of course, also potentially lead to phishing or other scam sites, rather than malware.

How do web links work?

The element that connects one website to another is called a hyperlink, or link for short. Links contain a web address (sometimes called a URL or URI), which begins with https:// or http://, followed by a domain name. They sometimes lead to a specific page on that site.

Web addresses can display in two ways. If you see one in a text message or an email sent in plain text format, you might see the full address, such as https://www.intego.com — and it may or may not appear as a clickable link. But if the link is on a web page or embedded in an HTML email, you’ll usually see an underlined link, with whatever text the sender wants to appear. As an example, this link to The Intego Mac Security Blog displays the text I chose, and hidden behind that is the actual link to the site.

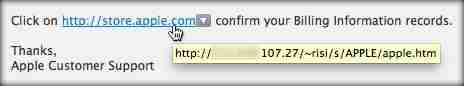

It’s also possible for that text itself to appear as a URL—which may or may not match the actual link destination, so beware. Anyone can make a link that displays one thing and hides another. Whether the link displays text or a URL, it could be deceptive. For example, I could create a link that says Get Free Stuff Here, but whose hidden link is something sinister. Hover your cursor over the link (if your computer has a mouse or trackpad), or tap and hold it on an iPhone or iPad to see the actual URL where it will take you.

How to see where a link will take you

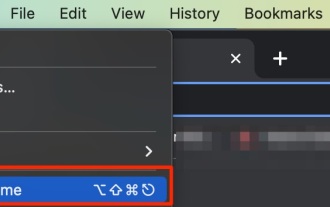

Just above, you practiced the first technique you need to know to tell whether a link is safe: hover your cursor over the link, or tap and hold it on an iPhone or iPad. This works in Mail, in Messages, or, as in the screenshot above, in a PDF that I exported containing this article. In a web browser, the URL behind a link often displays in the browser’s status bar; in Safari for Mac, choose View > Show Status Bar. In most other browsers like Chrome, Edge, and Firefox, the URL displays above the bottom-left corner of the browser window when you hover.

But seeing the URL when you do this isn’t always enough to know if a link is safe. Sometimes links can be deceptive. I recently received an email claiming to be from Apple, saying I was due a refund for AppleCare from an iPhone I traded in several years ago. This seemed suspicious—though it turned out to be legitimate. The first thing I did was hover my cursor over the link in the email.

To my surprise, the link didn’t go to apple.com, but to apple.co. I happen to know that Apple owns that domain, but I had never seen Apple use it in links, and I don’t know why the company did in this case. When I clicked the link, it didn’t redirect to the page it should have, so I called Apple support to get more information, and pointed out that my first reaction was that this looked like a phishing email.

When in doubt, go to an existing bookmark to the site in your browser. Or, if you don’t have it bookmarked, type the known website address manually. Then look for the section that is mentioned in the emails or message you received; you may have to sign into the site first. If you can’t find it, contact the company’s support team. Avoid doing a Google or other web search for a site; the top link may be a deceptive advertisement that looks like the company’s homepage but actually leads somewhere else.

What to look for in links

There are many things to look for to determine if links are safe or malicious.

How link domains and URLs are spelled

The first thing to look for in links is misspellings and variations of legitimate domain names. For example, if you see applle.com, you should assume that it’s an attempt to fool you. Also, app1e.com, which contains the digit 1 instead of the letter l, can look correct in some fonts. A domain like apple-web.com could also be a malicious site that Apple doesn’t own.

There can also be hyphens as part of actual domains, such as my-site.com. Beware that hyphens can be used to deceive; for example, if someone used support-apple.com, notice that the actual domain isn’t apple.com. It’s not even a subdomain, like the legitimate Apple site support.apple.com. Rather, “support-apple.com” is a site that doesn’t belong to Apple.

Another type of deceptive URL is one where a domain is faked with extra words separated by dots. For example, you may see a link to apple.refund.com. In this example, the real domain is refund.com, and the apple part is merely a subdomain (a site associated with the refund.com domain).

Top-level domains (the “dot-something” at the end)

Domain names all begin with a number of characters, and end with .com, .net, .edu, .me, and now hundreds of other possibilities. The “dot something” part at the end of a domain is called the top-level domain, or TLD for short. Most major brands and retailers use .com, or country-specific TLDs such as .fr (France), .de (Germany), or .co.uk (United Kingdom).

Watch out for domains that look like short URLs, such as app.le; you shouldn’t assume that Apple owns this.

HTTPS, or domains that support encryption

You should always be wary of links that go to URLs that begin with http:// rather than https://. The latter, HTTPS, is the secure version of the HTTP protocol that is used for websites. HTTPS ensures that data between your device and the website is encrypted.

Most websites today use HTTPS, and any that don’t could be dodgy. Most web browsers will warn you if you try to load a website that doesn’t use HTTPS, and you should not continue to those sites. You can often tell that a website is secure when your browser displays a padlock in its address bar.

Some old sites that haven’t been updated to HTTPS and might no longer be in use, and hackers may get access to these sites and use them to host malicious web pages.

Having said all that, the presence of https:// or a padlock doesn’t mean the site is actually safe or legitimate. In fact, most malicious sites use HTTPS these days. HTTPS only implies a secure connection between your browser and the web server. But if you have an HTTPS connection to a hacker’s site, the HTTPS doesn’t protect you from anything malicious on that site.

Tracker domains

It’s not uncommon for links in emails to not go to the actual domain they appear to; the links could be created via email services to track clicks. One example is the commonly used MailChimp service. You may receive a newsletter sent by MailChimp, and, if you hover over a link in that email, you’ll see their domain. When you click this link it redirects to another website; MailChimp’s servers forward your request to the real sender’s domain. This isn’t dangerous, but threat actors (bad guys) could also use MailChimp, or send emails with links that look like MailChimp, to try to fool you.

Extra words in the link after the domain name

Sometimes, you’ll get an email with a link where the domain could be anything, but the text after the domain is intended to fool you, as in this example:

Numerical IP addresses

The domain might even be a numerical IP address, rather than an actual domain, followed by text after that IP address that falsely suggests it may come from a particular company:

As a general rule, beware of URLs that contain lots of numbers, what seem like random letters and numbers, or multiple hyphens, which could be designed to trick you.

And any link containing an IP address, such as 192.123.456.789, instead of a spelled-out domain name, is likely to be dangerous.

Complex domains

Scammers sometimes use complex domains, assuming that people won’t understand them.

This is another common deceptive tactic, similar to the ones we’ve described previously. More than a couple dots in a domain name, like the presence of hyphens, should be viewed as suspicious and a possible attempt to deceive.

File-extension lookalike TLDs

You are probably familiar with files ending in .zip and .mov; these typically represent compressed archives and movie or video files, respectively. Unfortunately, these have also become publicly available top-level domains, available to scammers. You might see a link in an email or text message to file.zip or movie.mov; they could be links to domains that are trying to scam you.

Some other less common file name extensions are also available as TLDs, such as .sh, .pl, and .rs. (As file names, these represent shell scripts, or Perl or Rust documents, respectively.)

How to check links

When in doubt, you can use link checkers which can help you determine whether links you receive might be secure or not. Some examples of link-checking sites include URLVoid, VirusTotal, Google Safe Browsing, and urlscan.io, which has a live feed of URLs that people check. URLVoid and VirusTotal each check multiple domain blacklists—more than 110, after deduplication.

These link-checking sites aren’t foolproof, of course; new domains are registered all the time, and these services may not yet know about brand-new phishing or malware sites at the time you check them. But if any of these link checkers hint that a URL you scan might be malicious, it’s best to avoid visiting it.

Shortened domains, and other redirect URLs

Be especially wary of shortened URLs, using domains such as bit.ly, goo.gl, t.co, and others. When you click one of these links, the shortening services redirect you to the original link, and this could be malicious. There are tools you can use to check shortened URLs; try ExpandURL, for example, where you can enter a shortened URL and see where it goes. Or use Link Unshortener, a Mac app that can show you the path of any shortened URL.

Even redirect-checker services aren’t foolproof, however; redirect links can lead to different destinations depending on factors such as the visitor’s browser, operating system, or perceived geographical location. So, for example, if it looks like you’re using a Windows PC in Russia, you might be redirected to a harmless site, while if you’re using a Mac in the United States, you might be redirected to a malware or phishing site.

Clicking malicious links can, of course, be harmful. There are a lot of ways that links can trick people, so it’s important to know what to look for. When in doubt, don’t click. Go directly to the real website with which the link claims to be associated (ideally via a bookmark) and search for the page or information the link purports to offer.

The above is the detailed content of Is this link safe? How to check safely—without clicking on it. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

Video Face Swap

Swap faces in any video effortlessly with our completely free AI face swap tool!

Hot Article

Hot Tools

Notepad++7.3.1

Easy-to-use and free code editor

SublimeText3 Chinese version

Chinese version, very easy to use

Zend Studio 13.0.1

Powerful PHP integrated development environment

Dreamweaver CS6

Visual web development tools

SublimeText3 Mac version

God-level code editing software (SublimeText3)

Hot Topics

1664

1664

14

14

1423

1423

52

52

1317

1317

25

25

1268

1268

29

29

1243

1243

24

24

Fix your Mac running slow after update to Sequoia

Apr 14, 2025 am 09:30 AM

Fix your Mac running slow after update to Sequoia

Apr 14, 2025 am 09:30 AM

After upgrading to the latest macOS, does the Mac run slower? Don't worry, you are not alone! This article will share my experience in solving slow Mac running problems after upgrading to macOS Sequoia. After the upgrade, I can’t wait to experience new features such as recording and transcription of voice notes and improved trail map planning capabilities. But after installation, my Mac started running slowly. Causes and solutions for slow Mac running after macOS update Here is my summary of my experience, I hope it can help you solve the problem of slow Mac running after macOS Sequoia update: Cause of the problem Solution Performance issues Using Novabe

How to make a video into a live photo on Mac and iPhone: Detailed steps

Apr 11, 2025 am 10:59 AM

How to make a video into a live photo on Mac and iPhone: Detailed steps

Apr 11, 2025 am 10:59 AM

This guide explains how to convert between Live Photos, videos, and GIFs on iPhones and Macs. Modern iPhones excel at image processing, but managing different media formats can be tricky. This tutorial provides solutions for various conversions, al

How to reduce WindowServer Mac CPU usage

Apr 16, 2025 pm 12:07 PM

How to reduce WindowServer Mac CPU usage

Apr 16, 2025 pm 12:07 PM

macOS WindowServer: Understanding High CPU Usage and Solutions Have you noticed WindowServer consuming significant CPU resources on your Mac? This process is crucial for your Mac's graphical interface, rendering everything you see on screen. High C

How to type hashtag on Mac

Apr 13, 2025 am 09:43 AM

How to type hashtag on Mac

Apr 13, 2025 am 09:43 AM

You can’t really use the internet nowadays without encountering the hashtag symbol that looks like this — #. Popularized on a global scale by Twitter as a way to define common tweet themes and later adopted by Instagram and other apps to c

Is Google Chrome Not Working on Mac? Why Are Websites Not Loading?

Apr 12, 2025 am 11:36 AM

Is Google Chrome Not Working on Mac? Why Are Websites Not Loading?

Apr 12, 2025 am 11:36 AM

With a market share of over 65.7%, Google Chrome is the biggest web browser in the world. You can use it if you use other operating systems like Windows and Android, but many Mac users also prefer Chrome over Safari. Mo

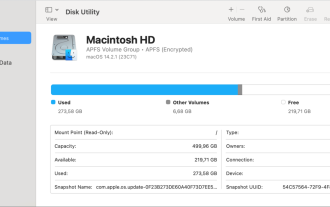

Mac Disk Utility: How to Repair Disk with First Aid? How to Recover It?

Apr 13, 2025 am 11:49 AM

Mac Disk Utility: How to Repair Disk with First Aid? How to Recover It?

Apr 13, 2025 am 11:49 AM

You might need to repair your Mac disk if your computer won’t start up, apps keep freezing, you can’t open certain documents, or the performance has slowed to a halt. Luckily, Apple includes a handy tool you can use to

How to delete files on Mac

Apr 15, 2025 am 10:22 AM

How to delete files on Mac

Apr 15, 2025 am 10:22 AM

Managing Mac storage: A comprehensive guide to deleting files Daily Mac usage involves installing apps, creating files, and downloading data. However, even high-end Macs have limited storage. This guide provides various methods for deleting unneces

How to connect bluetooth headphones to Mac?

Apr 12, 2025 pm 12:38 PM

How to connect bluetooth headphones to Mac?

Apr 12, 2025 pm 12:38 PM

From the dawn of time to just about a few years ago, all of us sported a pair of wired headphones and were convinced that this is simply how it will be done forever. After all, they are the easiest technology around: just plug them in, put them