Language memory management is an important aspect of language design. It is an important factor in determining language performance. Whether it is manual management in C language or garbage collection in Java, they have become the most important features of the language. Here, we take the Python language as an example to illustrate the memory management method of a dynamically typed, object-oriented language.

Memory usage of objects

The assignment statement is the most common function of the language. But even the simplest assignment statement can be very meaningful. Python’s assignment statement is worth studying.

a = 1

Integer1 is an object. And a is a reference. Using the assignment statement, reference a points to object 1. Python is a dynamically typed language (refer to dynamic typing), and objects and references are separated. Python uses "chopsticks" to touch and flip real food-objects through references.

References and Objects

In order to explore the storage of objects in memory, we can turn to Python's built-in function id(). It is used to return the identity of the object. In fact, the so-called identity here is the memory address of the object.

a = 1 print(id(a)) print(hex(id(a)))

On my computer, they return:

11246696

'0xab9c68'

are the memory addresses respectively Decimal and hexadecimal representation.

In Python, Python will cache these objects for integers and short characters for reuse. When we create multiple references equal to 1, we actually make all these references point to the same object.

a = 1 b = 1 print(id(a)) print(id(b))

The above program returns

11246696

11246696

It can be seen that a and b actually point to the same object of two references.

In order to check that two references point to the same object, we can use the is keyword. is is used to determine whether the objects pointed to by two references are the same.

# Truea = 1 b = 1 print(a is b) # True a = "good" b = "good" print(a is b) # False a = "very good morning" b = "very good morning" print(a is b) # False a = [] b = [] print(a is b)

The above comments are the corresponding running results. As you can see, since Python caches integers and short strings, only one copy of each object is stored. For example, all references to the integer 1 point to the same object. Even if you use an assignment statement, you only create a new reference, not the object itself. Long strings and other objects can have multiple identical objects, and new objects can be created using assignment statements.

In Python, each object has a total number of references pointing to the object, that is, a reference count (reference count).

We can use getrefcount() in the sys package to view the reference count of an object. It should be noted that when a reference is passed as a parameter to getrefcount(), the parameter actually creates a temporary reference. Therefore, the result obtained by getrefcount() will be 1 more than expected.

from sys import getrefcount a = [1, 2, 3] print(getrefcount(a)) b = a print(getrefcount(b))

Due to the above reasons, the two getrefcounts will return 2 and 3 instead of the expected 1 and 2.

Object reference object

A container object (container) in Python, such as a table, dictionary, etc., can contain multiple objects. In fact, what the container object contains is not the element object itself, but a reference to each element object.

We can also customize an object and reference other objects:

class from_obj(object):

def init(self, to_obj):

self.to_obj = to_obj

b = [1,2,3]

a = from_obj(b)

print(id(a.to_obj))

print(id(b))

As you can see, a refers to object b.

Object reference object is the most basic way of structuring Python. Even the assignment method a = 1 actually makes an element with the key value "a" of the dictionary refer to the integer object 1. This dictionary object is used to record all global references. The dictionary references the integer object 1. We can view this dictionary through the built-in function globals().

When an object A is referenced by another object B, A's reference count will be increased by 1.

from sys import getrefcount a = [1, 2, 3] print(getrefcount(a)) b = [a, a] print(getrefcount(a))

Since object b references a twice, the reference count of a is increased by 2.

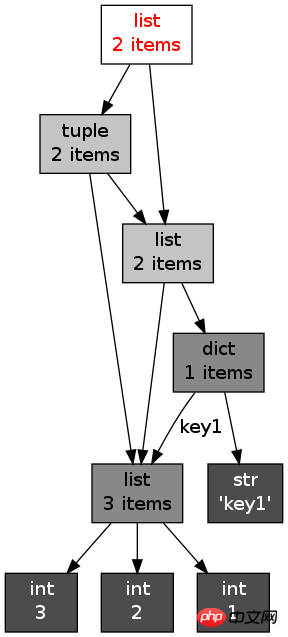

References to container objects may form very complex topological structures. We can use the objgraph package to draw its reference relationships, such as

x = [1, 2, 3] y = [x, dict(key1=x)] z = [y, (x, y)] import objgraph objgraph.show_refs([z], filename='ref_topo.png')

objgraph is a third-party package for Python. You need to install xdot before installation.

sudo apt-get install xdot sudo pip install objgraph

Two objects may reference each other, forming a so-called reference cycle.

a = [] b = [a] a.append(b)

Even an object that only needs to refer to itself can form a reference cycle.

a = [] a.append(a) print(getrefcount(a))

引用环会给垃圾回收机制带来很大的麻烦,我将在后面详细叙述这一点。

引用减少

某个对象的引用计数可能减少。比如,可以使用del关键字删除某个引用:

from sys import getrefcount a = [1, 2, 3] b = a print(getrefcount(b)) del a print(getrefcount(b))

del也可以用于删除容器元素中的元素,比如:

a = [1,2,3] del a[0] print(a)

如果某个引用指向对象A,当这个引用被重新定向到某个其他对象B时,对象A的引用计数减少:

from sys import getrefcount a = [1, 2, 3] b = a print(getrefcount(b)) a = 1 print(getrefcount(b))

垃圾回收

吃太多,总会变胖,Python也是这样。当Python中的对象越来越多,它们将占据越来越大的内存。不过你不用太担心Python的体形,它会乖巧的在适当的时候“减肥”,启动垃圾回收(garbage collection),将没用的对象清除。在许多语言中都有垃圾回收机制,比如Java和Ruby。尽管最终目的都是塑造苗条的提醒,但不同语言的减肥方案有很大的差异 (这一点可以对比本文和Java内存管理与垃圾回收)。

从基本原理上,当Python的某个对象的引用计数降为0时,说明没有任何引用指向该对象,该对象就成为要被回收的垃圾了。比如某个新建对象,它被分配给某个引用,对象的引用计数变为1。如果引用被删除,对象的引用计数为0,那么该对象就可以被垃圾回收。比如下面的表:

a = [1, 2, 3] del a

del a后,已经没有任何引用指向之前建立的[1, 2, 3]这个表。用户不可能通过任何方式接触或者动用这个对象。这个对象如果继续待在内存里,就成了不健康的脂肪。当垃圾回收启动时,Python扫描到这个引用计数为0的对象,就将它所占据的内存清空。

然而,减肥是个昂贵而费力的事情。垃圾回收时,Python不能进行其它的任务。频繁的垃圾回收将大大降低Python的工作效率。如果内存中的对象不多,就没有必要总启动垃圾回收。所以,Python只会在特定条件下,自动启动垃圾回收。当Python运行时,会记录其中分配对象(object allocation)和取消分配对象(object deallocation)的次数。当两者的差值高于某个阈值时,垃圾回收才会启动。

我们可以通过gc模块的get_threshold()方法,查看该阈值:

import gc print(gc.get_threshold())

返回(700, 10, 10),后面的两个10是与分代回收相关的阈值,后面可以看到。700即是垃圾回收启动的阈值。可以通过gc中的set_threshold()方法重新设置。

我们也可以手动启动垃圾回收,即使用gc.collect()。

分代回收

Python同时采用了分代(generation)回收的策略。这一策略的基本假设是,存活时间越久的对象,越不可能在后面的程序中变成垃圾。我们的程序往往会产生大量的对象,许多对象很快产生和消失,但也有一些对象长期被使用。出于信任和效率,对于这样一些“长寿”对象,我们相信它们的用处,所以减少在垃圾回收中扫描它们的频率。

Python将所有的对象分为0,1,2三代。所有的新建对象都是0代对象。当某一代对象经历过垃圾回收,依然存活,那么它就被归入下一代对象。垃圾回收启动时,一定会扫描所有的0代对象。如果0代经过一定次数垃圾回收,那么就启动对0代和1代的扫描清理。当1代也经历了一定次数的垃圾回收后,那么会启动对0,1,2,即对所有对象进行扫描。

这两个次数即上面get_threshold()返回的(700, 10, 10)返回的两个10。也就是说,每10次0代垃圾回收,会配合1次1代的垃圾回收;而每10次1代的垃圾回收,才会有1次的2代垃圾回收。

同样可以用set_threshold()来调整,比如对2代对象进行更频繁的扫描。

import gc gc.set_threshold(700, 10, 5)

孤立的引用环

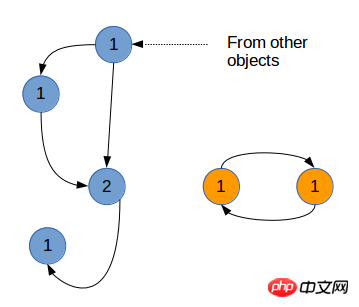

引用环的存在会给上面的垃圾回收机制带来很大的困难。这些引用环可能构成无法使用,但引用计数不为0的一些对象。

a = [] b = [a] a.append(b) del a del b

上面我们先创建了两个表对象,并引用对方,构成一个引用环。删除了a,b引用之后,这两个对象不可能再从程序中调用,就没有什么用处了。但是由于引用环的存在,这两个对象的引用计数都没有降到0,不会被垃圾回收。

孤立的引用环

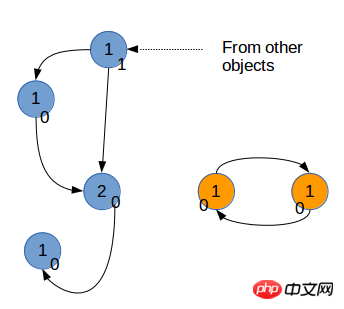

为了回收这样的引用环,Python复制每个对象的引用计数,可以记为gc_ref。假设,每个对象i,该计数为gc_ref_i。Python会遍历所有的对象i。对于每个对象i引用的对象j,将相应的gc_ref_j减1。

遍历后的结果

在结束遍历后,gc_ref不为0的对象,和这些对象引用的对象,以及继续更下游引用的对象,需要被保留。而其它的对象则被垃圾回收。

总结

Python作为一种动态类型的语言,其对象和引用分离。这与曾经的面向过程语言有很大的区别。为了有效的释放内存,Python内置了垃圾回收的支持。Python采取了一种相对简单的垃圾回收机制,即引用计数,并因此需要解决孤立引用环的问题。

Python与其它语言既有共通性,又有特别的地方。对该内存管理机制的理解,是提高Python性能的重要一步。

The above is the detailed content of Detailed introduction to python's memory management. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!