Python basics-class variables and instance variables

Python Basics - Class Variables and Instance Variables

Write in front

Unless otherwise specified, the following is based on Python3

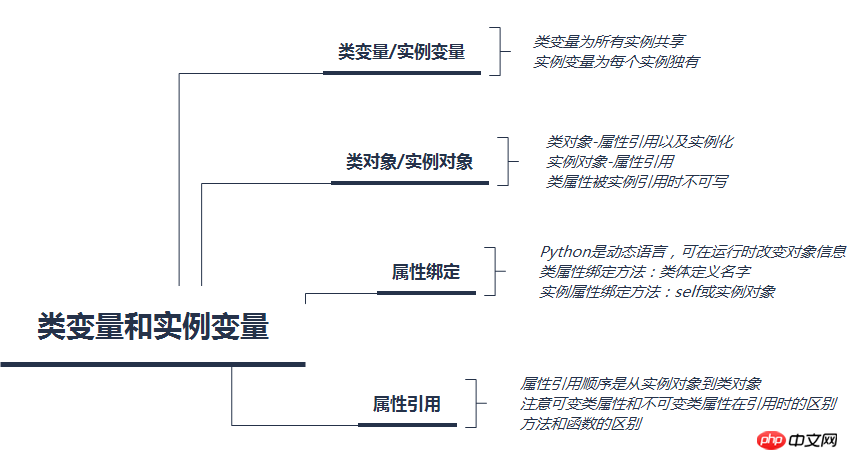

Outline:

1. Class variables and instance variables

In the Python Tutorial, class variables and instance variables are described like this:

Generally speaking, instance variables are for data unique to each instance and class variables are for attributes and methods shared by all instances of the class:

Generally speaking, instance variables are for each instance Unique data, while class variables are properties and methods shared by all instances of the class.

In fact, I prefer to use class attributes and instance attributes to call them, but variable has become a customary term for programming languages. A normal example is:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine' # class variable shared by all instancesdef __init__(self, name):self.name = name # instance variable unique to each instanceIn class Dog, the class attribute kind is shared by all instances; the instance attribute name is unique to each instance of Dog.

2. Class objects and instance objects

2.1 Class objects

Everything in Python is an object; after the class definition is completed, it will be in the current scope Define a name with the class name in it, pointing to the name of the class object. For example,

class Dog:pass

will define the name Dog in the current scope, pointing to the class object Dog.

Operations supported by class objects:

In general, class objects only support two operations:

instantiation; use

Instance_name = class_name()is instantiated, and the instantiation operation creates an instance of the class.Attribute reference; use

class_name.attr_nameto reference class attributes.

2.2 Instance object

The instance object is the product of class object instantiation. The instance object only supports one operation:

Attribute reference; in the same way as class object attribute reference, use

instance_name.attr_name.

According to strict object-oriented thinking, all attributes should be instances, and class attributes should not exist. Then in Python, since class attribute binding should not exist, only the function definition is left in the class definition.

The Python tutorial also says the same about class definitions:

In practice, the statements inside a class definition will usually be function definitions, but other statements are allowed, and sometimes useful.

In practice, the statements in a class definition are usually function definitions, but other statements are also allowed and sometimes useful.

The other statements mentioned here refer to the binding statements of class attributes.

3. Attribute binding

When defining a class, what we usually call defining attributes is actually divided into two aspects:

Class attribute binding

Instance attribute binding

The word binding is more precise; whether it is a class object It is still an instance object, and the properties all exist based on the object.

The attribute binding we are talking about requires a variable object first to perform the binding operation. Use the

objname.attr = attr_value

method to create the object objnameBinding attributesattr.

There are two situations:

If the attribute

attralready exists, the binding operation will point the attribute name to the new object;If it does not exist, add a new attribute to the object, and you can reference the new attribute later.

3.1 Class attribute binding

PythonAs a dynamic language, both class objects and instance objects can bind any attributes at runtime. Therefore, the binding of class attributes occurs in two places:

when the class is defined;

at any stage during runtime.

The following example illustrates the period when class attribute binding occurs:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine'Dog.country = 'China'print(Dog.kind, ' - ', Dog.country) # output: canine - Chinadel Dog.kindprint(Dog.kind, ' - ', Dog.country) # AttributeError: type object 'Dog' has no attribute 'kind'In the class definition, the binding of class attributes does not Use the method objname.attr = attr_value. This is a special case. It is actually equivalent to the method of binding attributes using class names later.

Because it is a dynamic language, attributes can be added and deleted at runtime.

3.2 Instance attribute binding

Same as class attribute binding, instance attribute binding also occurs in two places:

When the class is defined ;

Any stage during runtime.

Example:

class Dog:def __init__(self, name, age):self.name = nameself.age = age dog = Dog('Lily', 3) dog.fur_color = 'red'print('%s is %s years old, it has %s fur' % (dog.name, dog.age, dog.fur_color))# Output: Lily is 3 years old, it has red fur

PythonClass instances have two special features:

__init__Executed at instantiationPythonWhen an instance calls a method, the instance object will be used as the first parameter Pass

Therefore, self in the __init__ method is the instance object itself, here is dog, statement

self.name = nameself.age = age

以及后面的语句

dog.fur_color = 'red'

为实例dog增加三个属性name, age, fur_color。

4. 属性引用

属性的引用与直接访问名字不同,不涉及到作用域。

4.1 类属性引用

类属性的引用,肯定是需要类对象的,属性分为两种:

数据属性

函数属性

数据属性引用很简单,示例:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine'Dog.country = 'China'print(Dog.kind, ' - ', Dog.country) # output: canine - China通常很少有引用类函数属性的需求,示例:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine'def tell_kind():print(Dog.kind)

Dog.tell_kind() # Output: canine函数tell_kind在引用kind需要使用Dog.kind而不是直接使用kind,涉及到作用域,这一点在我的另一篇文章中有介绍:Python进阶 - 命名空间与作用域

4.2 实例属性引用

使用实例对象引用属性稍微复杂一些,因为实例对象可引用类属性以及实例属性。但是实例对象引用属性时遵循以下规则:

总是先到实例对象中查找属性,再到类属性中查找属性;

属性绑定语句总是为实例对象创建新属性,属性存在时,更新属性指向的对象。

4.2.1 数据属性引用

示例1:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine'country = 'China'def __init__(self, name, age, country):self.name = nameself.age = ageself.country = country

dog = Dog('Lily', 3, 'Britain')print(dog.name, dog.age, dog.kind, dog.country)# output: Lily 3 canine Britain类对象Dog与实例对象dog均有属性country,按照规则,dog.country会引用到实例对象的属性;但实例对象dog没有属性kind,按照规则会引用类对象的属性。

示例2:

class Dog:

kind = 'canine'country = 'China'def __init__(self, name, age, country):self.name = nameself.age = ageself.country = country

dog = Dog('Lily', 3, 'Britain')print(dog.name, dog.age, dog.kind, dog.country) # Lily 3 canine Britainprint(dog.__dict__) # {'name': 'Lily', 'age': 3, 'country': 'Britain'}dog.kind = 'feline'print(dog.name, dog.age, dog.kind, dog.country) # Lily 3 feline Britainprint(dog.__dict__)

print(Dog.kind) # canine 没有改变类属性的指向# {'name': 'Lily', 'age': 3, 'country': 'Britain', 'kind': 'feline'}使用属性绑定语句dog.kind = 'feline',按照规则,为实例对象dog增加了属性kind,后面使用dog.kind引用到实例对象的属性。

这里不要以为会改变类属性Dog.kind的指向,实则是为实例对象新增属性,可以使用查看__dict__的方式证明这一点。

示例3,可变类属性引用:

class Dog:

tricks = []def __init__(self, name):self.name = namedef add_trick(self, trick):self.tricks.append(trick)

d = Dog('Fido')

e = Dog('Buddy')

d.add_trick('roll over')

e.add_trick('play dead')print(d.tricks) # ['roll over', 'play dead']语句self.tricks.append(trick)并不是属性绑定语句,因此还是在类属性上修改可变对象。

4.2.2 方法属性引用

与数据成员不同,类函数属性在实例对象中会变成方法属性。

先看一个示例:

class MethodTest:def inner_test(self):print('in class')def outer_test():print('out of class') mt = MethodTest() mt.outer_test = outer_testprint(type(MethodTest.inner_test)) # <class 'function'>print(type(mt.inner_test)) #<class 'method'>print(type(mt.outer_test)) #<class 'function'>

可以看到,类函数属性在实例对象中变成了方法属性,但是并不是实例对象中所有的函数都是方法。

Python tutorial中这样介绍方法对象:

When an instance attribute is referenced that isn’t a data attribute, its class is searched. If the name denotes a valid class attribute that is a function object, a method object is created by packing (pointers to) the instance object and the function object just found together in an abstract object: this is the method object. When the method object is called with an argument list, a new argument list is constructed from the instance object and the argument list, and the function object is called with this new argument list.

引用非数据属性的实例属性时,会搜索它对应的类。如果名字是一个有效的函数对象,Python会将实例对象连同函数对象打包到一个抽象的对象中并且依据这个对象创建方法对象:这就是被调用的方法对象。当使用参数列表调用方法对象时,会使用实例对象以及原有参数列表构建新的参数列表,并且使用新的参数列表调用函数对象。

那么,实例对象只有在引用方法属性时,才会将自身作为第一个参数传递;调用实例对象的普通函数,则不会。

所以可以使用如下方式直接调用方法与函数:

mt.inner_test() mt.outer_test()

除了方法与函数的区别,其引用与数据属性都是一样的

5. 最佳实践

虽然Python作为动态语言,支持在运行时绑定属性,但是从面向对象的角度来看,还是在定义类的时候将属性确定下来。

The above is the detailed content of Python basics-class variables and instance variables. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

Hot AI Tools

Undresser.AI Undress

AI-powered app for creating realistic nude photos

AI Clothes Remover

Online AI tool for removing clothes from photos.

Undress AI Tool

Undress images for free

Clothoff.io

AI clothes remover

AI Hentai Generator

Generate AI Hentai for free.

Hot Article

Hot Tools

Notepad++7.3.1

Easy-to-use and free code editor

SublimeText3 Chinese version

Chinese version, very easy to use

Zend Studio 13.0.1

Powerful PHP integrated development environment

Dreamweaver CS6

Visual web development tools

SublimeText3 Mac version

God-level code editing software (SublimeText3)

Hot Topics

Is there any mobile app that can convert XML into PDF?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 08:54 PM

Is there any mobile app that can convert XML into PDF?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 08:54 PM

An application that converts XML directly to PDF cannot be found because they are two fundamentally different formats. XML is used to store data, while PDF is used to display documents. To complete the transformation, you can use programming languages and libraries such as Python and ReportLab to parse XML data and generate PDF documents.

How to control the size of XML converted to images?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 07:24 PM

How to control the size of XML converted to images?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 07:24 PM

To generate images through XML, you need to use graph libraries (such as Pillow and JFreeChart) as bridges to generate images based on metadata (size, color) in XML. The key to controlling the size of the image is to adjust the values of the <width> and <height> tags in XML. However, in practical applications, the complexity of XML structure, the fineness of graph drawing, the speed of image generation and memory consumption, and the selection of image formats all have an impact on the generated image size. Therefore, it is necessary to have a deep understanding of XML structure, proficient in the graphics library, and consider factors such as optimization algorithms and image format selection.

Is the conversion speed fast when converting XML to PDF on mobile phone?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 10:09 PM

Is the conversion speed fast when converting XML to PDF on mobile phone?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 10:09 PM

The speed of mobile XML to PDF depends on the following factors: the complexity of XML structure. Mobile hardware configuration conversion method (library, algorithm) code quality optimization methods (select efficient libraries, optimize algorithms, cache data, and utilize multi-threading). Overall, there is no absolute answer and it needs to be optimized according to the specific situation.

How to convert XML files to PDF on your phone?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 10:12 PM

How to convert XML files to PDF on your phone?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 10:12 PM

It is impossible to complete XML to PDF conversion directly on your phone with a single application. It is necessary to use cloud services, which can be achieved through two steps: 1. Convert XML to PDF in the cloud, 2. Access or download the converted PDF file on the mobile phone.

How to open xml format

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:00 PM

How to open xml format

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:00 PM

Use most text editors to open XML files; if you need a more intuitive tree display, you can use an XML editor, such as Oxygen XML Editor or XMLSpy; if you process XML data in a program, you need to use a programming language (such as Python) and XML libraries (such as xml.etree.ElementTree) to parse.

Recommended XML formatting tool

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:03 PM

Recommended XML formatting tool

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:03 PM

XML formatting tools can type code according to rules to improve readability and understanding. When selecting a tool, pay attention to customization capabilities, handling of special circumstances, performance and ease of use. Commonly used tool types include online tools, IDE plug-ins, and command-line tools.

Is there a mobile app that can convert XML into PDF?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:45 PM

Is there a mobile app that can convert XML into PDF?

Apr 02, 2025 pm 09:45 PM

There is no APP that can convert all XML files into PDFs because the XML structure is flexible and diverse. The core of XML to PDF is to convert the data structure into a page layout, which requires parsing XML and generating PDF. Common methods include parsing XML using Python libraries such as ElementTree and generating PDFs using ReportLab library. For complex XML, it may be necessary to use XSLT transformation structures. When optimizing performance, consider using multithreaded or multiprocesses and select the appropriate library.

What is the function of C language sum?

Apr 03, 2025 pm 02:21 PM

What is the function of C language sum?

Apr 03, 2025 pm 02:21 PM

There is no built-in sum function in C language, so it needs to be written by yourself. Sum can be achieved by traversing the array and accumulating elements: Loop version: Sum is calculated using for loop and array length. Pointer version: Use pointers to point to array elements, and efficient summing is achieved through self-increment pointers. Dynamically allocate array version: Dynamically allocate arrays and manage memory yourself, ensuring that allocated memory is freed to prevent memory leaks.