Ishanu Chattopadhyay, an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, told Insider that he and his team created an "urban twin" model by analyzing Chicago's crime data from 2014 to the end of 2016. Training, can predict the likelihood of certain crimes in the coming weeks and narrow it down to a two-block radius with 90% accuracy.

Chattopadhyay said, "We report a method for predicting urban crime at the individual incident level with far higher predictive accuracy. in the past. "

"We demonstrated that discovering city-specific crime patterns is useful for predicting crime reports," James Evans, co-author of the paper, told Science Daily importance, which generates a new view of urban communities, allows us to ask novel questions, and allows us to evaluate police operations in new ways."

The research was published in Nature Human Behavior.

##Paper link:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-022-01372-0

The data for the model comes from historical data for the city of Chicago, which includes two broad categories of reported incidents: violent crime (murder, assault, and battery) and property crime (burglary, theft, and motor vehicle theft).

Chicago’s crime rate in 2020 was 67% higher than the national average, according to data compiled by AreaVibes.

This data is used because it is most likely to be reported to police in urban areas where there has been a history of distrust and lack of contact with police. Cooperation with law enforcement.

#Unlike drug crimes, traffic stops and other minor offenses, these crimes are also less prone to law enforcement bias.

# By testing and validating the data, the new model trained can accurately predict the pattern of events in the coming weeks by observing the time and spatial coordinates of discrete events. , the geographical scope can be controlled to about two blocks.

##The model is available in seven other cities (Atlanta, Austin, Detroit, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Portland and San Francisco .) also obtained similar results, focusing primarily on the type of crime and where it occurred.

"We create a digital twin of an urban environment. If you feed it data from what happened in the past, it tells you what will happen in the future, "It's not magic, there are some limitations, but we verified it and it worked really well," Chattopadhyay said.

Potential biasLead author Ishanu Chattopadhyay is careful to note that “the tool’s accuracy does not mean it should be used to guide law enforcement policy—for example, police departments should not use it to proactively gather Some community to prevent crime,” Chattopadhyay said.

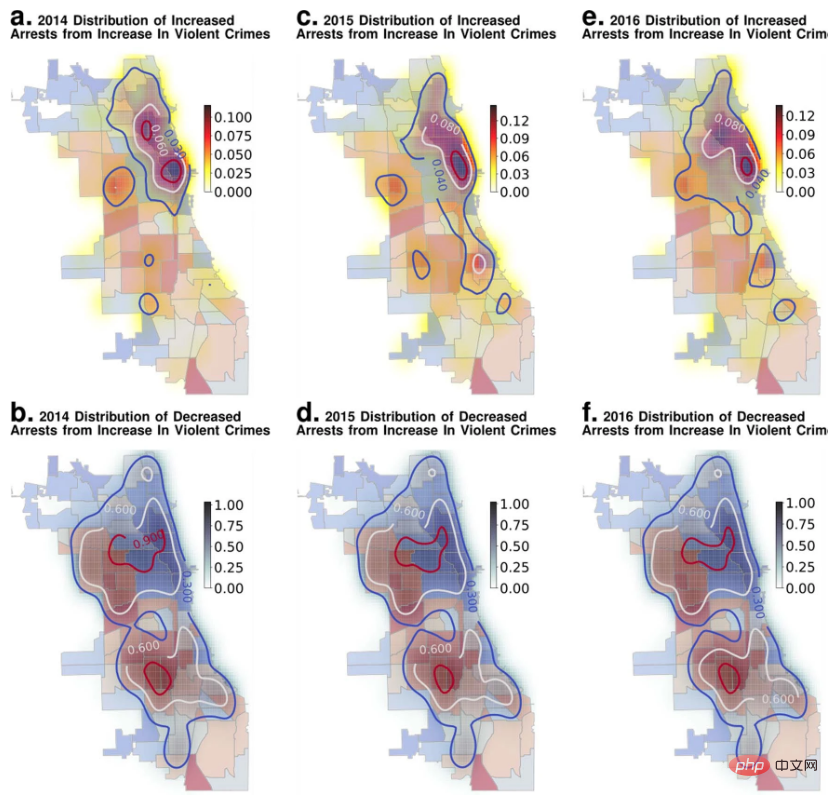

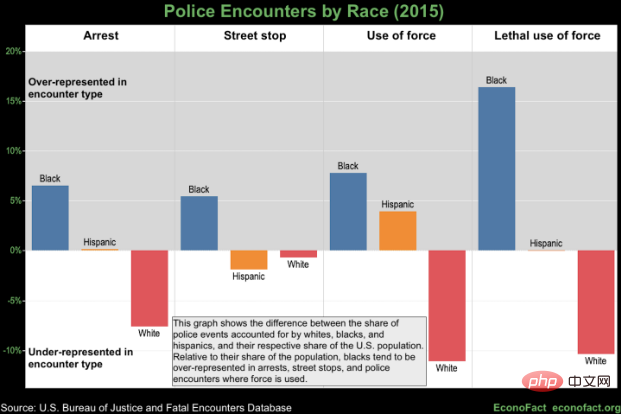

# Instead, it should be added to the toolbox of urban policy and policing strategies to address crime. "Now, you can use it as a simulation tool to see what would happen if crime increased in one area of the city, or if law enforcement increased in another area. What if You apply all these different variables and you can see how the system responds to them," explains Chattopadhyay. The research team also studied police responses to crime by analyzing the number of arrests made after an incident and comparing arrest rates in different communities. Racial bias in policing imposes high economic costs and exacerbates inequality in areas already suffering from severe deprivation, according to research compiled by Econofact . They found that when crime rates rise in wealthy areas, more people are arrested. But this is not happening in disadvantaged communities, which shows that police response and enforcement are uneven. Therefore, Chattopadhyay made these data and algorithms public to strengthen review, he hopes the findings will be used for high-level policy rather than as a police response tool. #Despite this, there are still many doubts about such research. #In 2016, the Chicago Police Department experimented with a model to predict those most likely to be involved in shootings, but the mysterious list ultimately revealed, Fifty-six percent of black men living in Chicago were on the list, sparking accusations of racism. While some models attempt to eradicate these biases, they often have the opposite effect, with some accusing racial bias in the underlying data of fueling future prejudicial behavior. Lawrence Sherman of the Cambridge Center for Evidence-Based Policing told New Scientist he was concerned the study would include policing data that relied on citizen reporting or The police are out in search of criminal behavior. Chattopadhyay agrees that this is a problem, and his team attempts to do so by excluding citizen-reported crimes and police intervention, which often involve minor drug offenses and traffic stops. and more serious violent and property crimes (which are more likely to be reported in any case) to explain this. Chattopadhyay said: “Ideally, if you can predict or prevent crime, the only response shouldn’t be to send more police or have law enforcement in large numbers. flock to a particular community." "If you can prevent crime, there are a lot of other things we can do to prevent this type of thing from happening so Someone will go to jail and help society as a whole."

The above is the detailed content of Nature sub-journal: New algorithm can predict crime within two blocks a week in advance, with an accuracy of 90% in 8 US cities. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!

Page replacement algorithm

Page replacement algorithm

js gets current time

js gets current time

What does pycharm mean when running in parallel?

What does pycharm mean when running in parallel?

css3transition

css3transition

Introduction to the main work content of front-end engineers

Introduction to the main work content of front-end engineers

How to connect php to mssql database

How to connect php to mssql database

The difference between Hongmeng system and Android system

The difference between Hongmeng system and Android system

How to open the download permission of Douyin

How to open the download permission of Douyin

tim mobile online

tim mobile online