AOP is aspect-oriented programming. Simply put, it is the programming idea of dynamically cutting the code into the specified method and designated position of the class, which is aspect-oriented programming.

We call the code snippet that cuts into a specified method of a specified class as an aspect, and which classes and methods are cut into are called entry points. In this way, we can extract the code common to several classes into a slice, and then cut into the object when needed, thereby changing its original behavior.

This kind of thinking can make the original code logic clearer and non-invasive to the original code. It is often used for permission management, logging, transaction management, etc.

The decorator in Python is a very famous design and is often used in scenarios with aspect requirements.

For example, Django uses a large number of decorators to complete various aspects of requirements, such as permission control, content filtering, request management, etc.

Python decorator (fuctional decorators) is a function used to expand the functionality of the original function, with the purpose of not changing the original function name or class name. , add new functionality to the function.

Let’s learn more about how decorators work with me.

First of all, we need to clarify a concept: everything in Python is an object, and functions are also objects!

So, a function as an object can be defined in another function. Look at the following example:

def a():

def b():

print("I'm b")

b()

c = b

return c

d = a()

d()

b()

c()The output result is:

I'm b

I'm b

Throws NameError: name 'b' is not defined error

throws NameError: name 'c' is not defined error

As can be seen from the above, since the function is an object, so:

Can be assigned to a variable

Can be defined in another function

Then,return Can return a function object. This function object is defined within another function. Due to different scopes, only the function returned by return can be called, and the functions b and c defined and assigned in function a act externally. The domain cannot be called.

This means that one function can return another function.

In addition to being returned as an object, a function object can also be passed as a parameter to another function:

def a():

print("I'm a")

def b(func):

print("I'm b")

func()

b(a)Output result:

I'm b

I'm a

OK, now, based on these characteristics of the function, we can create a decorator to use it without changing the original function. case, the function is implemented.

For example, if we want to perform some other operations before and after the function is executed, then according to the above function, it can be passed as a parameter. We can implement it like this. See the example below. :

def a():

print("I'm a")

def b(func):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

func()

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

b(a)Output result:

Before the function is executed, do some operations

I'm a

After the function is executed, do some operations Operation

But in this case, the original function becomes another function. Every time a function is added, a new layer of functions must be wrapped outside, so that all the original calling places need to be modified. , this is obviously inconvenient, and you will wonder if there is a way to change the operation of the function, but the name will not change, and it will still be used as the original function.

Look at the following example:

def a():

print("I'm a")

def c(func):

def b():

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

func()

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return b

a = c(a)

a()Output result:

Before the function is executed, do some operations

I'm a

After the function is executed, do some operations

As above, we can wrap the function in another layer and return the new function b as an object . In this way, through the function c, a is changed and reassigned to a, thus changing the function a and using the same function a to call.

But this is very inconvenient to write because it requires reassignment, so in Python, it can be achieved by @ and the function is passed as a parameter.

Look at the example:

def c(func):

def b():

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

func()

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return b

@c

def a():

print("I'm a")

a()Output result:

Do some operations before the function is executed

I'm a

After the function is executed, do some operations

As above, through @c, the function a is implemented as a parameter, Pass in c and recast the returned function as function a. This c is also a simple function decorator.

And if the function has a return value, then the changed function also needs to have a return value, as follows:

def c(func):

def b():

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func()

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

@c

def a():

print("函数执行中。。。")

return "I'm a"

print(a())Output result:

Do some operations before the function is executed.

The function is executing. . .

After the function is executed, do some operations

I'm a

如上所示:通过将返回值进行传递,就可以实现函数执行前后的操作。但是你会发现一个问题,就是为什么输出 I'm a 会在最后才打印出来?

因为 I'm a 是返回的结果,而实际上函数是 print("在函数执行后,做一些操作") 这一操作前运行的,只是先将返回的结果给到了 result,然后 result 传递出来,最后由最下方的 print(a()) 打印了出来。

那如何函数 a 带参数怎么办呢?很简单,函数 a 带参数,那么我们返回的函数也同样要带参数就好啦。

看下面示例:

def c(func):

def b(name, age):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(name, age)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

@c

def a(name, age):

print("函数执行中。。。")

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a('Amos', 24))输出结果:

在函数执行前,做一些操作

函数执行中。。。

在函数执行后,做一些操作

我是 Amos, 今年24岁

但是又有问题了,我写一个装饰器 c,需要装饰多个不同的函数,这些函数的参数各不相同,那么怎么办呢?简单,用 *args 和 **kwargs 来表示所有参数即可。

如下示例:

def c(func):

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

@c

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

@c

def d(sex, height):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return '性别:{},身高:{}'.format(sex, height)

print(a('Amos', 24))

print(d('男', 175))输出结果:

在函数执行前,做一些操作

函数执行中。。。

在函数执行后,做一些操作

我是 Amos, 今年24岁在函数执行前,做一些操作

函数执行中。。。

在函数执行后,做一些操作

性别:男,身高:175

如上就解决了参数的问题,哇,这么好用。那是不是这样就没有问题了?并不是!经过装饰器装饰后的函数,实际上已经变成了装饰器函数 c 中定义的函数 b,所以函数的元数据则全部改变了!

如下示例:

def c(func):

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

@c

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a.__name__)输出结果:

b

会发现函数实际上是函数 b 了,这就有问题了,那么该怎么解决呢,有人就会想到,可以在装饰器函数中先把原函数的元数据保存下来,在最后再讲 b 函数的元数据改为原函数的,再返回 b。这样的确是可以的!但我们不这样用,为什么?

因为 Python 早就想到这个问题啦,所以给我们提供了一个内置的方法,来自动实现原数据的保存和替换工作。哈哈,这样就不同我们自己动手啦!

看下面示例:

from functools import wraps

def c(func):

@wraps(func)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

@c

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a.__name__)输出结果:

a

使用内置的 wraps 装饰器,将原函数作为装饰器参数,实现函数原数据的保留替换功能。

耶!装饰器还可以带参数啊,你看上面 wraps 装饰器就传入了参数。哈哈,是的,装饰器还可以带参数,那怎么实现呢?

看下面示例:

from functools import wraps

def d(name):

def c(func):

@wraps(func)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

return c

@d(name='我是装饰器参数')

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a('Amos', 24))输出结果:

装饰器传入参数为:我是装饰器参数

在函数执行前,做一些操作

函数执行中。。。

在函数执行后,做一些操作

我是 Amos, 今年24岁

如上所示,很简单,只需要在原本的装饰器之上,再包一层,相当于先接收装饰器参数,然后返回一个不带参数的装饰器,然后再将函数传入,最后返回变化后的函数。

这样就可以实现很多功能了,这样可以根据传给装饰器的参数不同,来分别实现不同的功能。

另外,可能会有人问, 可以在同一个函数上,使用多个装饰器吗?答案是:可以!

看下面示例:

from functools import wraps

def d(name):

def c(func):

@wraps(func)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('我是装饰器d: 在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("我是装饰器d: 在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

return c

def e(name):

def c(func):

@wraps(func)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('我是装饰器e: 在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("我是装饰器e: 在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

return c

@e(name='我是装饰器e')

@d(name='我是装饰器d')

def func_a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(func_a('Amos', 24))

行后,做一些操作

我是 Amos, 今年24岁输出结果:

装饰器传入参数为:我是装饰器e

我是装饰器e: 在函数执行前,做一些操作装饰器传入参数为:我是装饰器d

我是装饰器d: 在函数执行前,做一些操作

函数执行中。。。

我是装饰器d: 在函数执行后,做一些操作我是装饰器e: 在函数执

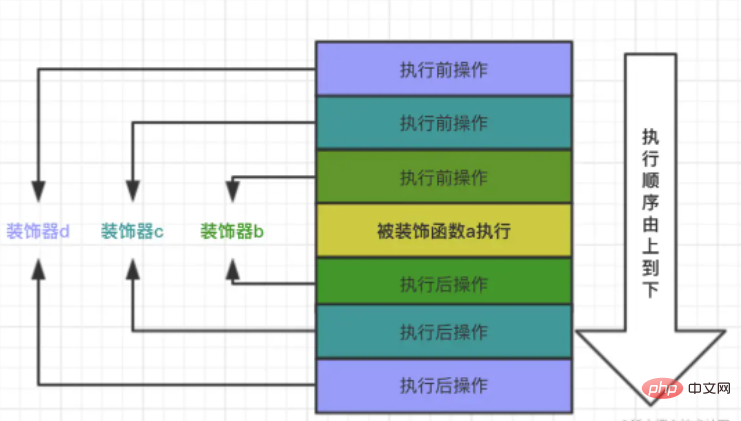

如上所示,当两个装饰器同时使用时,可以想象成洋葱,最下层的装饰器先包装一层,然后一直到最上层装饰器,完成多层的包装。然后执行时,就像切洋葱,从最外层开始,只执行到被装饰函数运行时,就到了下一层,下一层又执行到函数运行时到下一层,一直到执行了被装饰函数后,就像切到了洋葱的中间,然后再往下,依次从最内层开始,依次执行到最外层。

示例:

当一个函数 a 被 b,c,d 三个装饰器装饰时,执行顺序如下图所示,多个同理。

@d

@c

@b

def a():

pass

在函数装饰器方面,很多人搞不清楚,是因为装饰器可以用函数实现(像上面),也可以用类实现。因为函数和类都是对象,同样可以作为被装饰的对象,所以根据被装饰的对象不同,一同有下面四种情况:

函数装饰函数

类装饰函数

函数装饰类

类装饰类

下面我们依次来说明一下这四种情况的使用。

from functools import wraps

def d(name):

def c(func):

@wraps(func)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return b

return c

@d(name='我是装饰器参数')

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a.__class__)

# 输出结果:

<class 'function'>此为最常见的装饰器,用于装饰函数,返回的是一个函数。

也就是通过类来实现装饰器的功能而已。通过类的 __call__ 方法实现:

from functools import wraps

class D(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self._name = name

def __call__(self, func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(self._name))

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return wrapper

@D(name='我是装饰器参数')

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a.__class__)

# 输出结果:

<class 'function'>以上所示,只是将用函数定义的装饰器改为使用类来实现而已。还是用于装饰函数,因为在类的 __call__ 中,最后返回的还是一个函数。

此为带装饰器参数的装饰器实现方法,是通过 __call__ 方法。

若装饰器不带参数,则可以将 __init__ 方法去掉,但是在使用装饰器时,需要 @D() 这样使用,如下:

from functools import wraps

class D(object):

def __call__(self, func):

@wraps(func)

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

print('在函数执行前,做一些操作')

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

print("在函数执行后,做一些操作")

return result

return wrapper

@D()

def a(name, age):

print('函数执行中。。。')

return "我是 {}, 今年{}岁 ".format(name, age)

print(a.__class__)

# 输出结果:

<class 'function'>如上是比较方便简答的,使用类定义函数装饰器,且返回对象为函数,元数据保留。

下面重点来啦,我们常见的装饰器都是用于装饰函数的,返回的对象也是一个函数,而要装饰类,那么返回的对象就要是类,且类的元数据等也要保留。

不怕丢脸的说,目前我还不知道怎么实现完美的类装饰器,在装饰类的时候,一般有两种方法:

返回一个函数,实现类在创建实例的前后执行操作,并正常返回此类的实例。但是这样经过装饰器的类就属于函数了,其无法继承,但可以正常调用创建实例。

如下:

from functools import wraps

def d(name):

def c(cls):

@wraps(cls)

def b(*args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('在类初始化前,做一些操作')

instance = cls(*args, **kwargs)

print("在类初始化后,做一些操作")

return instance

return b

return c

@d(name='我是装饰器参数')

class A(object):

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

print('类初始化实例,{} {}'.format(self.name, self.age))

a = A('Amos', 24)

print(a.__class__)

print(A.__class__)

# 输出结果:

装饰器传入参数为:我是装饰器参数

在类初始化前,做一些操作

类初始化实例,Amos 24

在类初始化后,做一些操作

<class '__main__.A'>

<class 'function'>如上所示,就是第一种方法。

接上文,返回一个类,实现类在创建实例的前后执行操作,但类已经改变了,创建的实例也已经不是原本类的实例了。

看下面示例:

def desc(name):

def decorator(aClass):

class Wrapper(object):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

print('装饰器传入参数为:{}'.format(name))

print('在类初始化前,做一些操作')

self.wrapped = aClass(*args, **kwargs)

print("在类初始化后,做一些操作")

def __getattr__(self, name):

print('Getting the {} of {}'.format(name, self.wrapped))

return getattr(self.wrapped, name)

def __setattr__(self, key, value):

if key == 'wrapped': # 这里捕捉对wrapped的赋值

self.__dict__[key] = value

else:

setattr(self.wrapped, key, value)

return Wrapper

return decorator

@desc(name='我是装饰器参数')

class A(object):

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

print('类初始化实例,{} {}'.format(self.name, self.age))

a = A('Amos', 24)

print(a.__class__)

print(A.__class__)

print(A.__name__)输出结果:

装饰器传入参数为:我是装饰器参数

在类初始化前,做一些操作

类初始化实例,Amos 24

在类初始化后,做一些操作.decorator. .Wrapper'>

Wrapper

如上,看到了吗,通过在函数中新定义类,并返回类,这样函数还是类,但是经过装饰器后,类 A 已经变成了类 Wrapper,且生成的实例 a 也是类 Wrapper 的实例,即使通过 __getattr__ 和 __setattr__ 两个方法,使得实例a的属性都是在由类 A 创建的实例 wrapped 的属性,但是类的元数据无法改变。很多内置的方法也就会有问题。我个人是不推荐这种做法的!

所以,我推荐在代码中,尽量避免类装饰器的使用,如果要在类中做一些操作,完全可以通过修改类的魔法方法,继承,元类等等方式来实现。如果避免不了,那也请谨慎处理。

The above is the detailed content of How to use aspect-oriented programming AOP and decorators in Python. For more information, please follow other related articles on the PHP Chinese website!