아이들을 위한 프로그래밍 언어로 컴퓨터 만들기

... 즉, 임베디드 시스템에 들어가는 가장 멍청한 방법입니다.

여기에서 실제 모습을 감상하세요!

목표

목표는 간단했습니다. C나 C++로 코드를 작성하고 스크래치에서 실행할 수 있습니다. 솔직히 말해서, 가장 느린 프로그래밍 언어 중 가장 빠른 프로그래밍 언어 중 하나라는 아이디어가 꽤 재미있다고 생각했습니다. 가능하다는 느낌이 들었지만 어떻게 될지는 잘 모르겠습니다. 그 과정에서 예상했던 것보다 어셈블리 언어, 프로세스 메모리, 실행 파일에 대해 훨씬 더 많이 배웠고, 제 여정을 회상하면서 새로운 것을 배우셨으면 좋겠습니다.

0단계: 계획 세우기

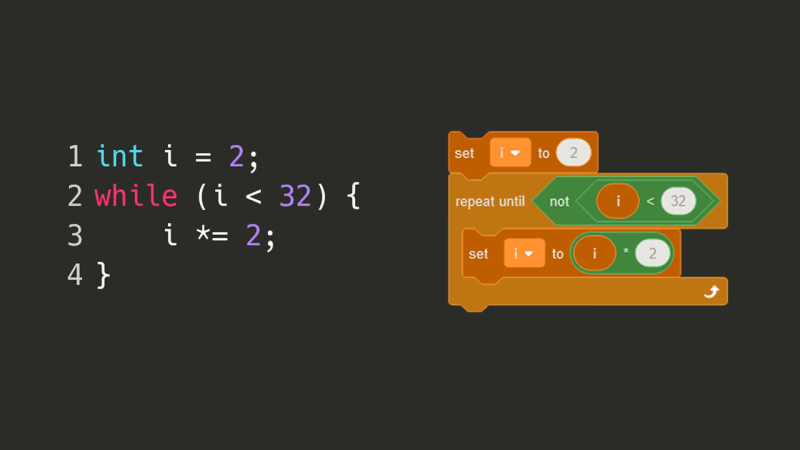

첫 번째 아이디어는 C로 작성한 코드를 여러 조각으로 나눈 다음 스크래치를 사용하여 그 조각들을 다시 합치는 것이었습니다. 예를 들어 C의 while 루프는 스크래치의 블록까지 반복이 될 수 있습니다.

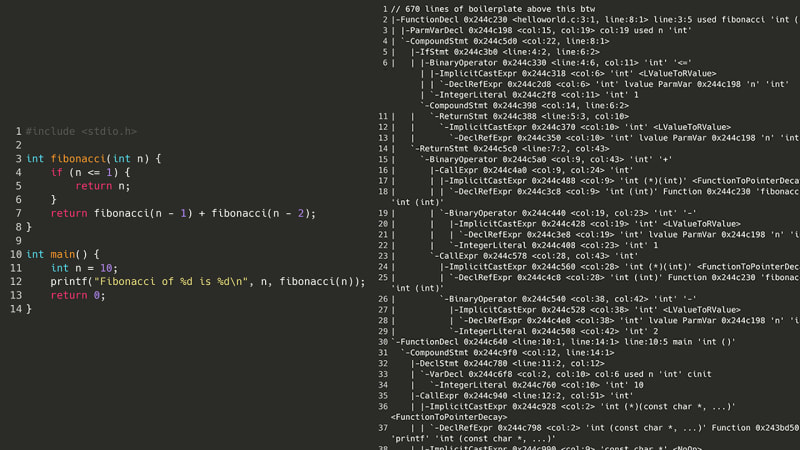

C 컴파일러가 코드를 이해하려면 먼저 소스 코드의 각 중요한 기호를 트리로 표현한 AST(추상 구문 트리)를 생성해야 합니다. 예를 들어 여는 괄호, 변수 이름 또는 return 키워드는 각각 고유 노드로 변환될 수 있습니다. 그런데 간단한 피보나치 수 프로그램을 위해 AST를 살펴보니…

0b단계: (더 나은) 계획 수립

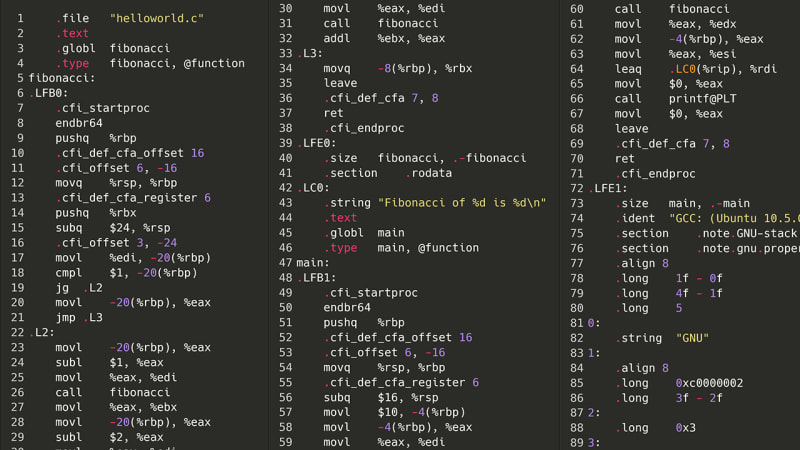

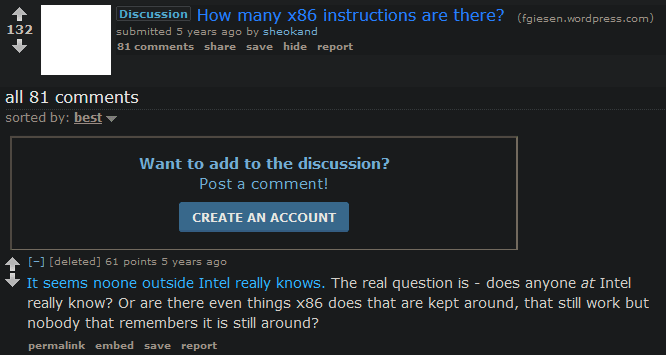

그건 불가능했습니다. 하지만 소스 코드를 다시 컴파일하는 대신 한 단계 아래로 내려가면 어떻게 될까요? 즉, 어셈블리일까요? 프로그램을 실행하려면 먼저 어셈블리로 컴파일해야 합니다. 내 컴퓨터에서는 x86-64asm입니다. 어셈블리에는 복잡한 중첩 구조, 클래스 또는 변수가 없기 때문에 어셈블리 명령 목록을 구문 분석하는 것은 (이론적으로) 위와 같은 AST의 스파게티 괴물을 구문 분석하는 것보다 쉽습니다. 다음은 동일한 Fibonacci 프로그램이지만 x86 어셈블리입니다.

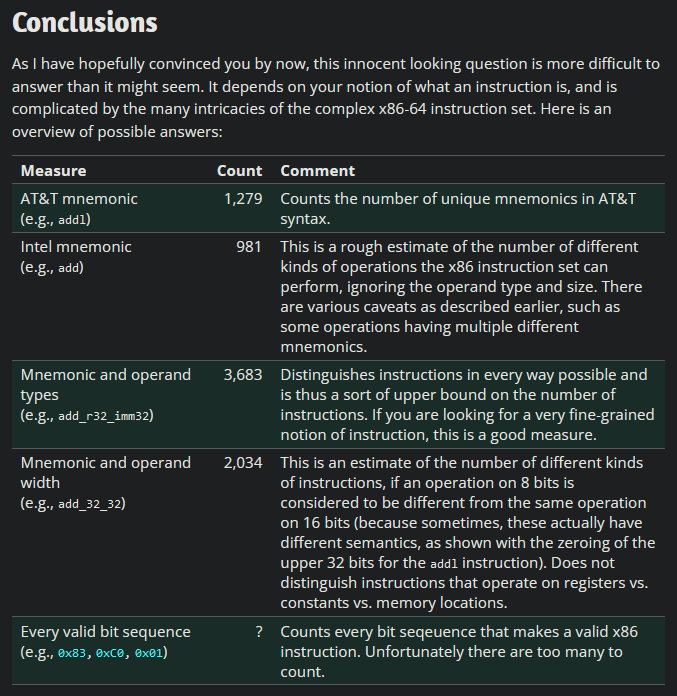

아, 형님. 좋아요, 아마도 그렇게 나쁘지는 않을 것 같아요. 총 지시사항은 몇 개인가요?

0c단계: 전체 계획

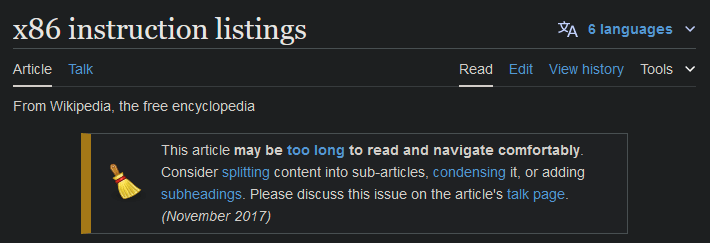

다행히 x86이 유일한 어셈블리 언어는 아닙니다. 나는 대학 수업의 일환으로 90년대부터 2000년대 초반까지 일부 비디오 게임 콘솔과 슈퍼컴퓨터에서 사용된 일종의 어셈블리 언어(지나치게 단순화된)인 MIPS에 대해 배웠으며 오늘날에도 여전히 일부 사용되고 있습니다. x86에서 MIPS로 전환하면 명령 수가 *알 수 없음*에서 약 50개로 줄어듭니다.

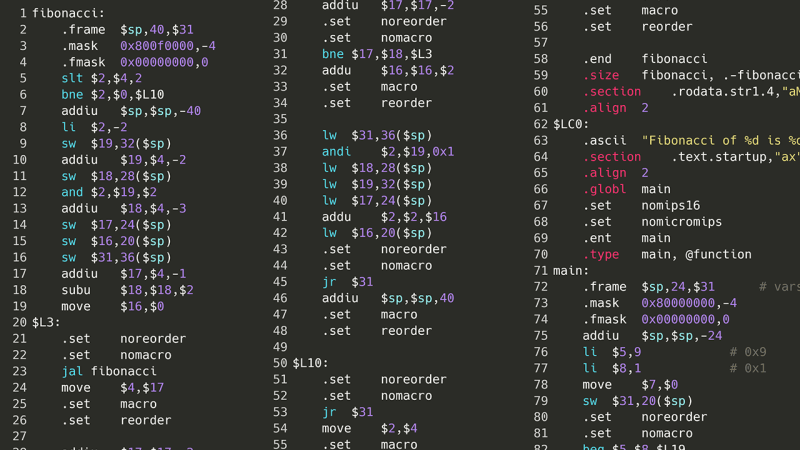

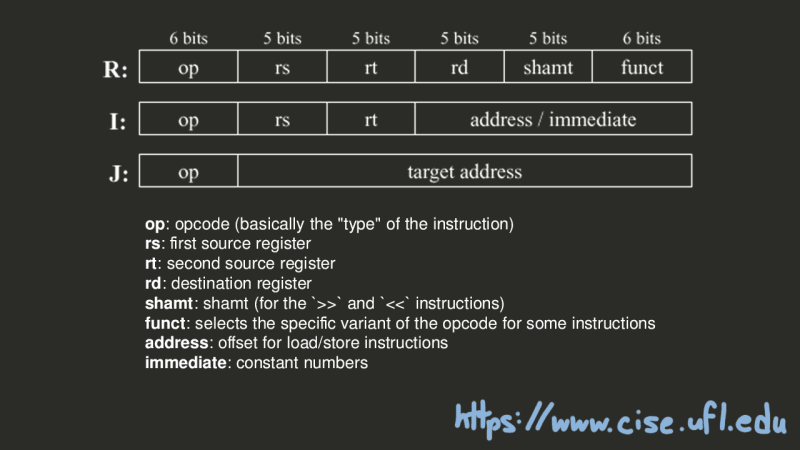

32비트 버전의 MIPS를 사용하면 이 어셈블리 코드를 기계어 코드로 변환할 수 있습니다. 여기서 각 명령어는 프로세서 아키텍처에서 설정한 지침에 따라 프로세서가 이해할 수 있는 32비트 정수로 변환됩니다. 온라인에서 구할 수 있는 MIPS 명령어 세트 아키텍처에 관한 책이 있습니다. 따라서 기계어 코드를 가져와서 MIPS 프로세서가 수행하는 작업을 정확하게 에뮬레이트하면 스크래치에서 C 코드를 실행할 수 있을 것입니다!

이제 문제가 해결되었으므로 시작할 수 있습니다.

1단계: 아직 시작할 수 없습니다.

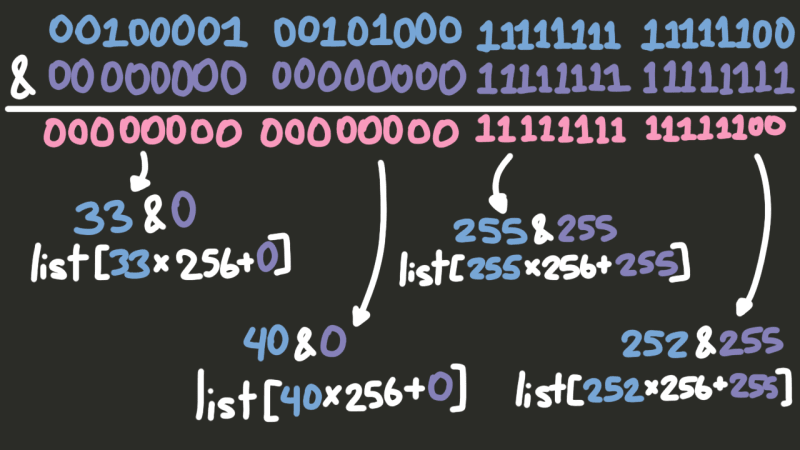

글쎄, 이미 문제가 있습니다. 일반적으로 정수가 있고 그로부터 일련의 비트를 추출하려는 경우 num & 마스크를 계산합니다. 여기서 마스크는 정수로, 중요한 비트는 각각 1이고 중요하지 않은 비트는 각각 0입니다.

001000 01001 01000 1111111111111100 & 000000 00000 00000 1111111111111111 -------------------------------------- 000000 0000 000000 1111111111111100

문제는? 스크래치에는 & 연산자가 없습니다.

이제 *단순히 두 숫자를 하나씩 살펴보고 두 비트의 가능한 네 가지 조합을 각각 확인할 수 있지만 시간이 너무 많이 걸립니다. 결국 이 작업은 *각 *명령에 대해 여러 번 수행되어야 합니다. 대신에 더 좋은 계획이 떠올랐어요.

먼저 0에서 255 사이의 모든 x와 모든 y에 대해 x & y를 계산하는 빠른 Python 스크립트를 작성했습니다.

for x in range(256):

for y in range(256):

print(x & y)

0 (0 & 0 == 0)

0 (0 & 1 == 0)

0 (0 & 2 == 0)

...

0 (0 & 255 == 0)

0 (1 & 0 == 0)

1 (1 & 1 == 1)

0 (1 & 2 == 0)

...

254 (255 & 254 == 254)

255 (255 & 255 == 255)

예를 들어, 두 개의 32비트 정수에 대한 x와 y를 계산하려면 다음을 수행할 수 있습니다.

Split x and y into four 8-bit integers (or bytes).

Check what first_byte_in_x & first_byte_in_y is by looking in the table generated from the Python script.

Similarly, look up what second_byte_in_x & second_byte_in_y is, and the third bytes, and the fourth bytes.

Take the results of each of these calculations, and put them together to get the result of x & y .

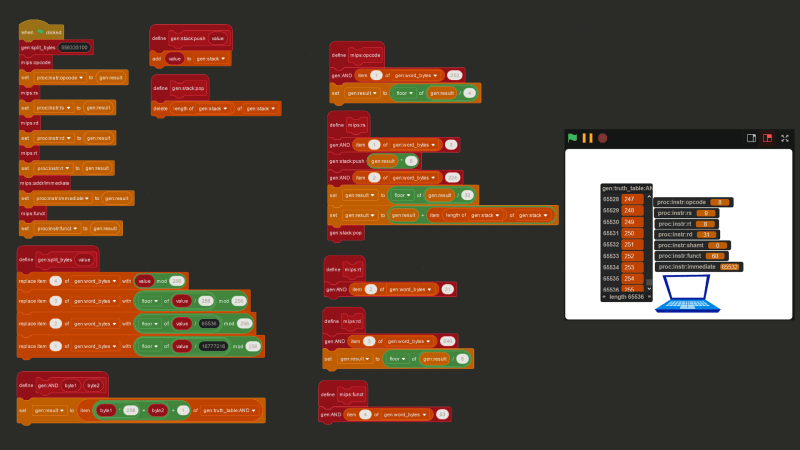

However, once a MIPS instruction has been cut up into four bytes, we’ll only & the bytes we need. For example, if we only need data from the first byte, we won’t even look at the bottom three. But how do we know which bytes we need? Based on the opcode (i.e. the “type”) of an instruction, MIPS will try to split up the bits of an instruction in one of three ways.

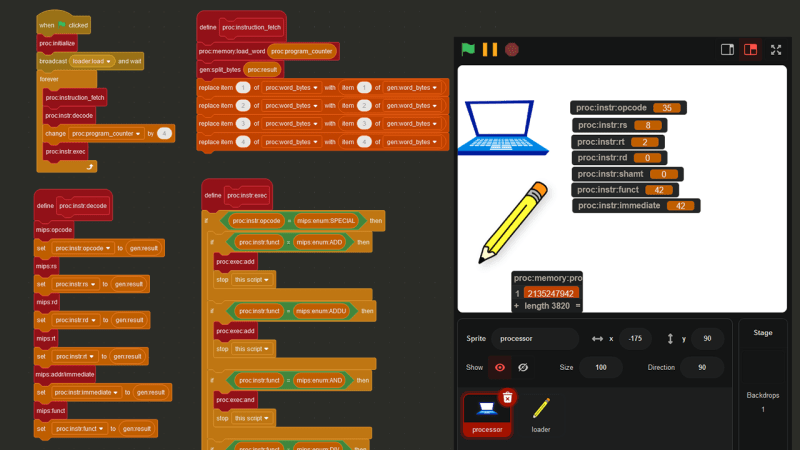

Putting everything together, below is the Scratch code to extract opcode, $rs, $rt, $rd, shamt, funct, and immediate for any instruction.

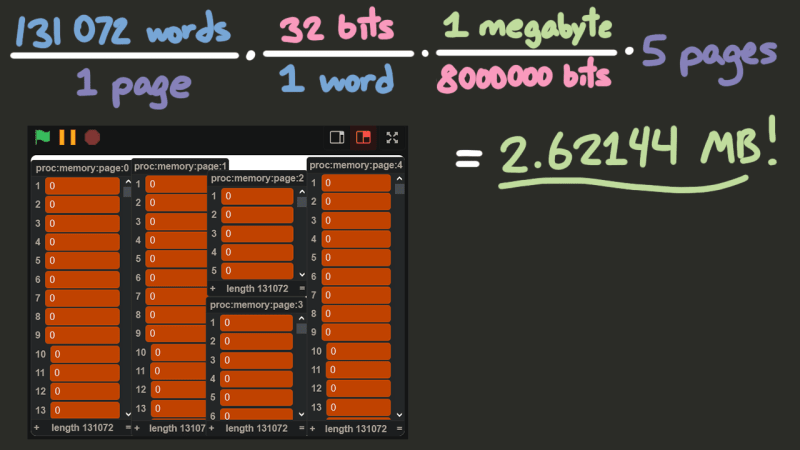

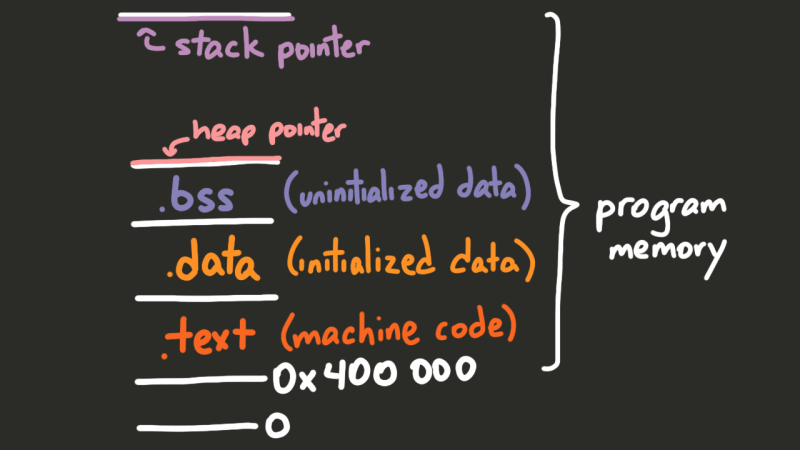

Step 2: A Short Word About Memory

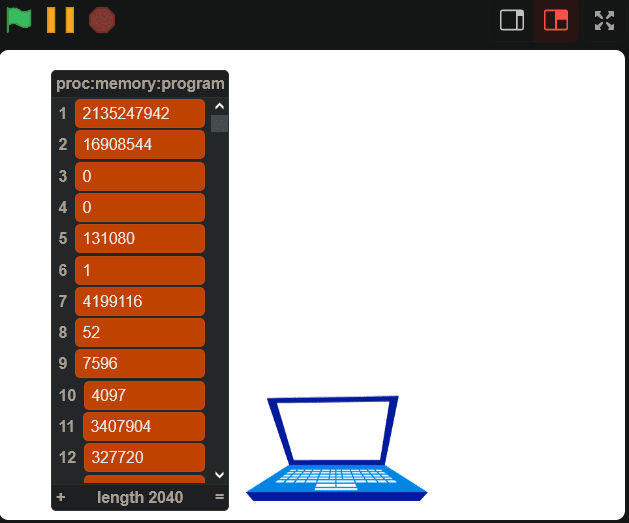

So, how much memory should our processor actually have? And how should we store it? Well, minimum, MIPS processors have 31 general-purpose registers, and one $zero register that is meant to store the number 0 at all times. A register is a location in memory that a processor can access quickly. We can represent these 32 registers as a list with 32 items in Scratch. As for the rest of the memory, simulating a processor moving chunks of data in and out of its cache in Scratch would be pretty pointless and would actually slow things down, rather than speed them up. So instead, the physical memory will be represented as five lists containing 131,072 elements each, where each element will be a 32-bit integer, giving us about 2.6MB of memory. A contiguous block of memory like these lists is usually called a “page”, and the size of the data that the instruction set works with (in this case 32 bits) is usually called a “word”.

Step 3: Visits from a Magical ELF

So, how do we get machine code in here? We can’t just import a file into Scratch. But we *can *import text! So, I wrote a program in C to take a binary executable file, and convert every 32 bytes of the file into an integer. C, by default, was reading each byte in little-endian, so I had to introduce a function to flip the endianness. Then, I can save the machine code of a program as a text file (a list of integers), and then import it into my proc:memory:program variable.

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned int flip_endian(unsigned int value) {

return ((value >> 24) & 0xff) | ((value >> 8) & 0xff00) | ((value << 8) & 0xff0000) | ((value << 24) & 0xff000000);

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc != 3 && argc != 2) {

printf("Usage: %s <input file> <output file?>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

FILE* in = fopen(argv[1], "r");

if (!in) {

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

unsigned int value;

FILE* out = argc == 3 ? fopen(argv[2], "w") : stdout;

if (!out) {

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

while (fread(&value, sizeof(value), 1, in) == 1) {

fprintf(out, "%u\n", flip_endian(value));

}

fclose(in);

if (out != stdout) {

fclose(out);

}

return 0;

}

Okay, so now that we can import the data into Scratch, we can just set the program counter (the integer keeping track of the current instruction) to the top of the list, and start executing instructions, right?

Wrong.

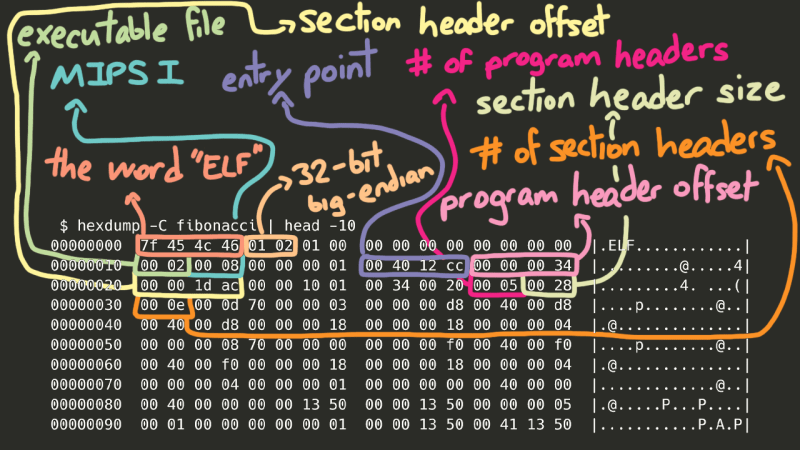

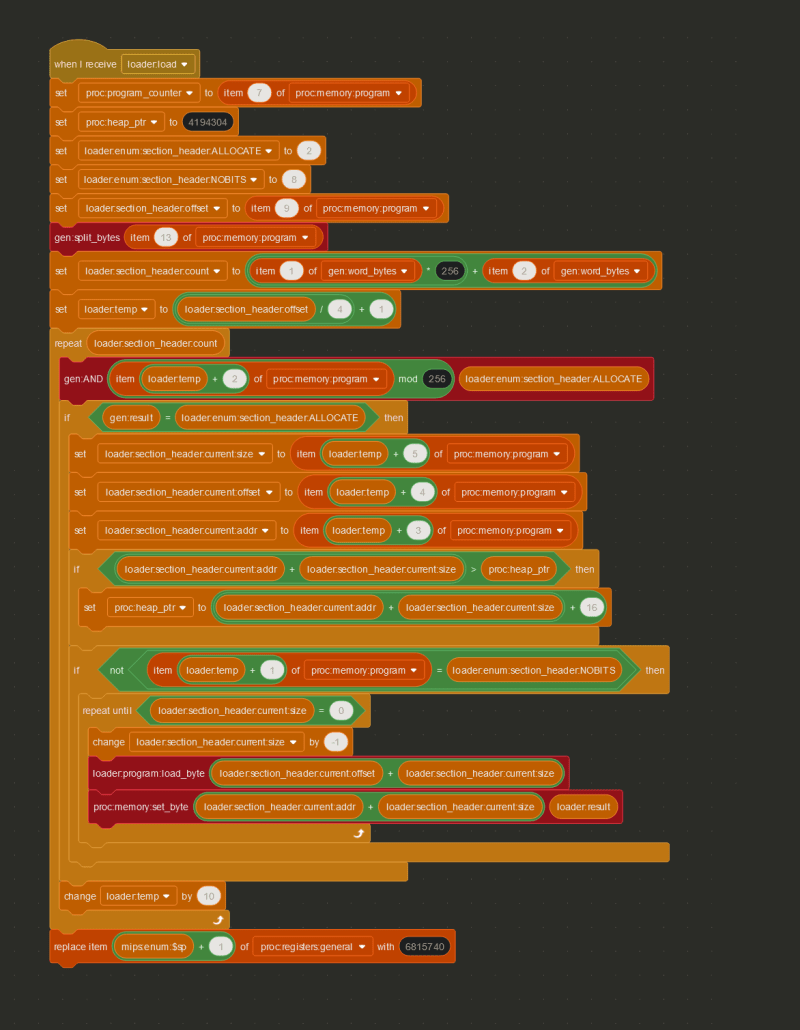

I didn’t realize this going into this project, but the first several bytes of an executable file *aren’t *instructions, but a header identifying what type of executable file it is. On Windows, it’ll usually be the PE, or Portable Executable, format, and on UNIX-based systems (the version we’ll be using) it’ll be the ELF format. So, how do we actually know where the code starts? On Linux, we can use the builtin readelf utility to actually see what’s in the ELF header, and the Linux Foundation has a page detailing the ELF header standard. So, we can use the LF page to figure out which bytes mean what, and the readelf command to “check our work”.

$ readelf -h fibonacci ELF Header: Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 01 02 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Class: ELF32 Data: 2's complement, big endian Version: 1 (current) OS/ABI: UNIX - System V ABI Version: 0 Type: EXEC (Executable file) Machine: MIPS R3000 Version: 0x1 Entry point address: 0x4012cc Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file) Start of section headers: 7596 (bytes into file) Flags: 0x1001, noreorder, o32, mips1 Size of this header: 52 (bytes) Size of program headers: 32 (bytes) Number of program headers: 5 Size of section headers: 40 (bytes) Number of section headers: 14 Section header string table index: 13

Now, there’s a lot of really interesting stuff here, but to save some time, the *really *important data here (besides the entry point, of course) are the section headers. Oversimplifying greatly, in order for our program to run correctly, we need to take certain chunks of the file and place them in certain parts of memory so our code can access them.

Using the readelf utility, we can actually see all of the sections in the file:

$ readelf -S fibonacci There are 14 section headers, starting at offset 0x1dac: Section Headers: [Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al [ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0 [ 1] .MIPS.abiflags MIPS_ABIFLAGS 004000d8 0000d8 000018 18 A 0 0 8 [ 2] .reginfo MIPS_REGINFO 004000f0 0000f0 000018 18 A 0 0 4 [ 3] .note.gnu.build-i NOTE 00400108 000108 000024 00 A 0 0 4 [ 4] .text PROGBITS 00400130 000130 001200 00 AX 0 0 16 [ 5] .rodata PROGBITS 00401330 001330 000020 00 A 0 0 16 [ 6] .bss NOBITS 00411350 001350 000010 00 WA 0 0 16 [ 7] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 001350 000029 01 MS 0 0 1 [ 8] .pdr PROGBITS 00000000 00137c 000440 00 0 0 4 [ 9] .gnu.attributes GNU_ATTRIBUTES 00000000 0017bc 000010 00 0 0 1 [10] .mdebug.abi32 PROGBITS 00000000 0017cc 000000 00 0 0 1 [11] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0017cc 000380 10 12 14 4 [12] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 001b4c 0001db 00 0 0 1 [13] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 001d27 000085 00 0 0 1 Key to Flags: W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info), L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS), C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude), p (processor specific)

Going through all the details of the ELF format could be its own multi-part write-up, but using the Linux Foundation page on section headers, I was able to decipher the section header bytes of the program, and copy all the important bytes from the proc:memory:program variable to the correct places in memory, by checking whether or not the section header had the ALLOCATE flag set.

Step 4: Cycling Through Instructions

Fast-forwarding about a week to the point where all of the important instructions have been implemented, let’s take a look at the steps the processor (or really, any processor) needs to take in order to understand just one instruction, using 0x8D02002A (2365718570) as an example.

The first step is called **INSTRUCTION FETCH. **The current instruction is retrieved from the address stored in the proc:program_counter variable.

The next step is INSTRUCTION DECODE, where the instruction is decoded into its separate parts (see Step 1).

Finally, we reach EXECUTE, which, in my Scratch processor, is pretty much just a big if statement.

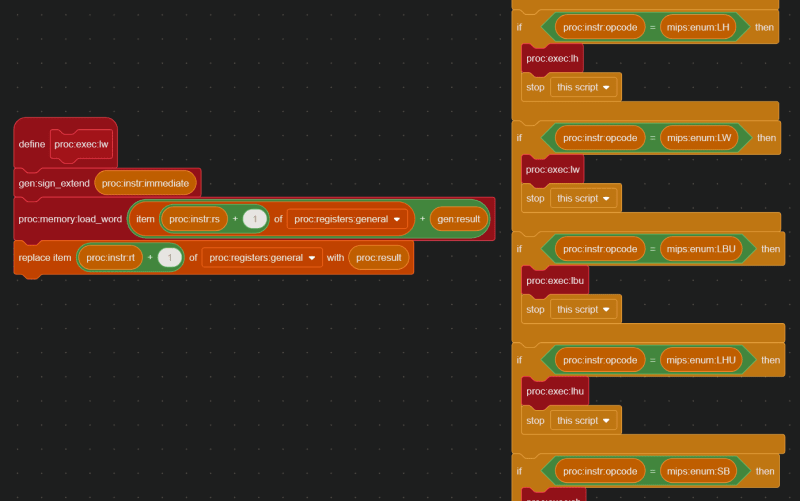

In this case, the INSTRUCTION DECODE step revealed that the opcode is 35, which means 0x8D02002A is a lw (load word) instruction. Therefore, based off the values in proc:instr:rs, proc:instr:rt, and proc:instr:immediate, the instruction 0x8D02002A actually means lw $2, 0x2a($8) , or in other words, lw $v0, 42($t0).

And here is the code that handles the lw instruction:

Step 5: Hello, World?

Okay, home stretch. Now, we just need to be able to do the bare minimum and create a “Hello, World” program in C, and run it in Scratch, and the last two weeks of my life will have been validated.

So, will this work?

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

Three changes. First of all, the MIPS linker uses start to find the entry point of the program, much the same way you use main in C, or "main__" in Python. So, that’s an easy fix.

#include <stdio.h>

int __start() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

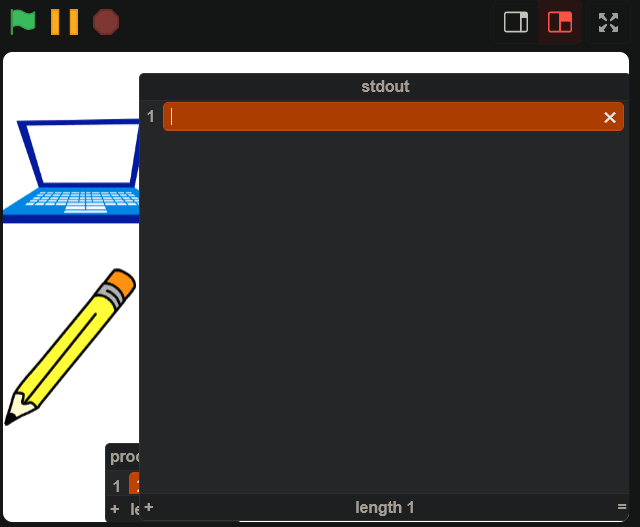

Next, we need some way to actually see this output in Scratch. We *could *make some intricate array of text sprites, but the simpler solution is just to use a list.

Finally, we can’t use stdio.h.

Yeah, basically, implementing floating point registers and multiprocessor instructions would have been more trouble than it was worth, so I skipped it, but the standard library kind of expects all that to be there. So, we need to make printf ourselves.

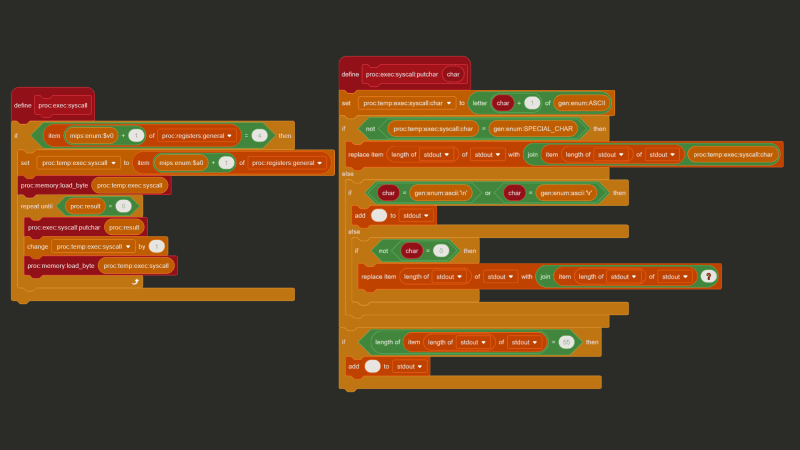

Putting the complications of variadic arguments and text formatting aside, how can you actually print a string using MIPS? The TL;DR is you put the address of the string in a certain register, and then a special “print string” value in another register, and then execute the syscall (“system call”) instruction, and let the OS/CPU handle the rest.

The exact special values and registers to use are implementation-dependent, and can be implemented pretty much any way you see fit, but I chose to replicate MARS’ (a very popular MIPS simulator) implementation. With MARS, the address of the string goes in $a0, and the value 4 goes in $v0 to say “hey, I want to print a string!”

And with C, we can use a feature called “inline assembly” to inject assembly code directly into our compiled output. Putting it all together we get this:

#define puts _puts

void _puts(const char *s) {

__asm__(

"li $v0, 4\n"

"syscall\n"

:

: "a"(s)

);

}

int __start() {

puts("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

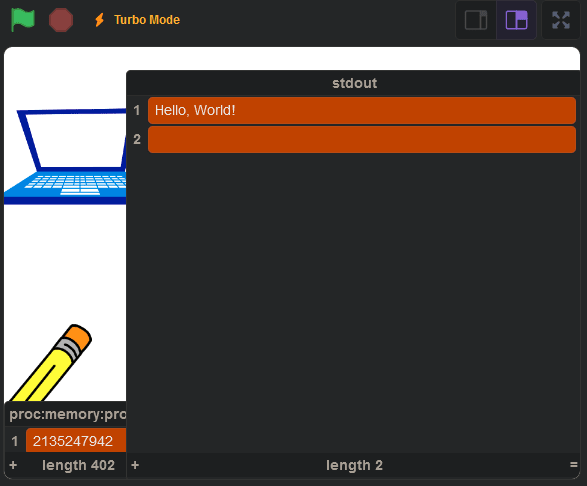

And when we run it, we get this:

Conclusion

You can view the final product here: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/1000840481/.

I wanted to keep this read under 15 minutes, so I had to skip over **a lot **of details. Some parts of the Scratch code had to be cut out of the screenshots for simplicity’s sake and I ran into a lot of silly and not-so-silly mistakes. If you’re curious how I was able to get Connect Four working (with minimax and alpha-beta pruning), the source code is on my Github. Here’s a quick list of some of the other problems I ran into in development:

* The fact that my computer is little-endian, but MIPS is big-endian caused more issues than I'd like to admit * The `mult` instruction in MIPS is 32-bit multiplication, and multiplying two 32-bit integers can result in a 64-bit integer. Javascript (and as a result, Scratch) is incapable of storing a 64-bit integer without losing precision. * The `u` in the `addu` instruction and the `u` in the `sltu` instruction both stand for "unsigned", but mean completely different things. * As you may have noticed, functions in Scratch don't have return values. This was quite annoying. * Any branch instruction (like "jump", "jump register", "branch on equals") in MIPS will also execute the instruction immediately after it, **regardless** of if the branch was taken or not. So, instead of updating the program count directly, the next address needs to be put in the "branch delay slot" and the program counter should only be updated after the *next* instruction. * Lists in Scratch are one-indexed. * All of a sudden, Scratch stopped letting me save the project to the cloud. It took awhile before I realized that lists filled with over 100,000 items wasn't something Scratch's servers were particularly excited to store. * I had to design my own `malloc` in C, which was fun, but also very difficult to debug in Scratch. * When I tried making syscalls that asked the user for input, all of the letters ended up capitalized. It turns out that in Scratch a lowercase `"a"` and a capital `"A"` are considered equal. I thought this was an unsolvable problem for awhile, before I realized that the names of sprites' costumes in Scratch are actually case-sensitive. So every time I try to convert a character to its ASCII value, I tell the processor sprite to switch to, for example, the `"a"` costume or the `"A"` costume, and then retrieve the costume number. * I made another syscall to print emojis to the `stdout`, but some emojis are considered two characters long and other emojis are considered one character long. * Compiling any code that calls `malloc` with -O1 crashes the CPU. I still have no idea why this is the case. * Endianness is really hard to get right. I know I said this in the beginning of the list, but it's worth repeating.

With all that said, I’m really happy with the way this project turned out. If you found this interesting, please check out sharc, my graphics engine built completely in Typescript: https://www.sharcjs.org. Because clearly, if there’s one thing I know how to make, it’s questionable decisions.

위 내용은 아이들을 위한 프로그래밍 언어로 컴퓨터 만들기의 상세 내용입니다. 자세한 내용은 PHP 중국어 웹사이트의 기타 관련 기사를 참조하세요!

핫 AI 도구

Undresser.AI Undress

사실적인 누드 사진을 만들기 위한 AI 기반 앱

AI Clothes Remover

사진에서 옷을 제거하는 온라인 AI 도구입니다.

Undress AI Tool

무료로 이미지를 벗다

Clothoff.io

AI 옷 제거제

Video Face Swap

완전히 무료인 AI 얼굴 교환 도구를 사용하여 모든 비디오의 얼굴을 쉽게 바꾸세요!

인기 기사

뜨거운 도구

메모장++7.3.1

사용하기 쉬운 무료 코드 편집기

SublimeText3 중국어 버전

중국어 버전, 사용하기 매우 쉽습니다.

스튜디오 13.0.1 보내기

강력한 PHP 통합 개발 환경

드림위버 CS6

시각적 웹 개발 도구

SublimeText3 Mac 버전

신 수준의 코드 편집 소프트웨어(SublimeText3)

C# vs. C : 역사, 진화 및 미래 전망

Apr 19, 2025 am 12:07 AM

C# vs. C : 역사, 진화 및 미래 전망

Apr 19, 2025 am 12:07 AM

C#과 C의 역사와 진화는 독특하며 미래의 전망도 다릅니다. 1.C는 1983 년 Bjarnestroustrup에 의해 발명되어 객체 지향 프로그래밍을 C 언어에 소개했습니다. Evolution 프로세스에는 자동 키워드 소개 및 Lambda Expressions 소개 C 11, C 20 도입 개념 및 코 루틴과 같은 여러 표준화가 포함되며 향후 성능 및 시스템 수준 프로그래밍에 중점을 둘 것입니다. 2.C#은 2000 년 Microsoft에 의해 출시되었으며 C와 Java의 장점을 결합하여 진화는 단순성과 생산성에 중점을 둡니다. 예를 들어, C#2.0은 제네릭과 C#5.0 도입 된 비동기 프로그래밍을 소개했으며, 이는 향후 개발자의 생산성 및 클라우드 컴퓨팅에 중점을 둘 것입니다.

C# vs. C : 학습 곡선 및 개발자 경험

Apr 18, 2025 am 12:13 AM

C# vs. C : 학습 곡선 및 개발자 경험

Apr 18, 2025 am 12:13 AM

C# 및 C 및 개발자 경험의 학습 곡선에는 상당한 차이가 있습니다. 1) C#의 학습 곡선은 비교적 평평하며 빠른 개발 및 기업 수준의 응용 프로그램에 적합합니다. 2) C의 학습 곡선은 가파르고 고성능 및 저수준 제어 시나리오에 적합합니다.

C의 정적 분석이란 무엇입니까?

Apr 28, 2025 pm 09:09 PM

C의 정적 분석이란 무엇입니까?

Apr 28, 2025 pm 09:09 PM

C에서 정적 분석의 적용에는 주로 메모리 관리 문제 발견, 코드 로직 오류 확인 및 코드 보안 개선이 포함됩니다. 1) 정적 분석은 메모리 누출, 이중 릴리스 및 초기화되지 않은 포인터와 같은 문제를 식별 할 수 있습니다. 2) 사용하지 않은 변수, 데드 코드 및 논리적 모순을 감지 할 수 있습니다. 3) Coverity와 같은 정적 분석 도구는 버퍼 오버플로, 정수 오버플로 및 안전하지 않은 API 호출을 감지하여 코드 보안을 개선 할 수 있습니다.

C 및 XML : 관계와 지원 탐색

Apr 21, 2025 am 12:02 AM

C 및 XML : 관계와 지원 탐색

Apr 21, 2025 am 12:02 AM

C는 XML과 타사 라이브러리 (예 : TinyXML, Pugixml, Xerces-C)와 상호 작용합니다. 1) 라이브러리를 사용하여 XML 파일을 구문 분석하고 C- 처리 가능한 데이터 구조로 변환하십시오. 2) XML을 생성 할 때 C 데이터 구조를 XML 형식으로 변환하십시오. 3) 실제 애플리케이션에서 XML은 종종 구성 파일 및 데이터 교환에 사용되어 개발 효율성을 향상시킵니다.

C에서 Chrono 라이브러리를 사용하는 방법?

Apr 28, 2025 pm 10:18 PM

C에서 Chrono 라이브러리를 사용하는 방법?

Apr 28, 2025 pm 10:18 PM

C에서 Chrono 라이브러리를 사용하면 시간과 시간 간격을보다 정확하게 제어 할 수 있습니다. 이 도서관의 매력을 탐구합시다. C의 크로노 라이브러리는 표준 라이브러리의 일부로 시간과 시간 간격을 다루는 현대적인 방법을 제공합니다. 시간과 C 시간으로 고통받는 프로그래머에게는 Chrono가 의심 할 여지없이 혜택입니다. 코드의 가독성과 유지 가능성을 향상시킬뿐만 아니라 더 높은 정확도와 유연성을 제공합니다. 기본부터 시작합시다. Chrono 라이브러리에는 주로 다음 주요 구성 요소가 포함됩니다. std :: Chrono :: System_Clock : 현재 시간을 얻는 데 사용되는 시스템 클럭을 나타냅니다. STD :: 크론

C의 미래 : 적응 및 혁신

Apr 27, 2025 am 12:25 AM

C의 미래 : 적응 및 혁신

Apr 27, 2025 am 12:25 AM

C의 미래는 병렬 컴퓨팅, 보안, 모듈화 및 AI/기계 학습에 중점을 둘 것입니다. 1) 병렬 컴퓨팅은 코 루틴과 같은 기능을 통해 향상 될 것입니다. 2)보다 엄격한 유형 검사 및 메모리 관리 메커니즘을 통해 보안이 향상 될 것입니다. 3) 변조는 코드 구성 및 편집을 단순화합니다. 4) AI 및 머신 러닝은 C가 수치 컴퓨팅 및 GPU 프로그래밍 지원과 같은 새로운 요구에 적응하도록 촉구합니다.

C : 죽어 가거나 단순히 진화하고 있습니까?

Apr 24, 2025 am 12:13 AM

C : 죽어 가거나 단순히 진화하고 있습니까?

Apr 24, 2025 am 12:13 AM

c is nontdying; it'sevolving.1) c COMINGDUETOITSTIONTIVENICICICICINICE INPERFORMICALEPPLICATION.2) thelugageIscontinuousUllyUpdated, witcentfeatureslikemodulesandCoroutinestoimproveusActionalance.3) despitechallen

C# vs. C : 메모리 관리 및 쓰레기 수집

Apr 15, 2025 am 12:16 AM

C# vs. C : 메모리 관리 및 쓰레기 수집

Apr 15, 2025 am 12:16 AM

C#은 자동 쓰레기 수집 메커니즘을 사용하는 반면 C는 수동 메모리 관리를 사용합니다. 1. C#의 쓰레기 수집기는 메모리 누출 위험을 줄이기 위해 메모리를 자동으로 관리하지만 성능 저하로 이어질 수 있습니다. 2.C는 유연한 메모리 제어를 제공하며, 미세 관리가 필요한 애플리케이션에 적합하지만 메모리 누출을 피하기 위해주의해서 처리해야합니다.