It is not difficult to achieve uniform sampling on a sphere. Just use a normally distributed random variable to generate a three-dimensional vector and then unitize it.

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <random>

using namespace std;

int main()

{

std::default_random_engine gen;

std::normal_distribution<float> distrib(0.f, 1.f);

ofstream ofs("sphere.txt");

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

float x = distrib(gen);

float y = distrib(gen);

float z = distrib(gen);

float r = sqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z);

ofs << x / r << ' ' << y / r << ' ' << z / r << endl;

}

return 0;

}

But I don’t know if it meets the requirements between adjacent points. If you want to ensure that adjacent points are far away, you can learn from ideas such as jittering or stratified sampling.

Java version

import java.util.Random;

import java.io.*;

class SphericalSampling{

public static void main(String[] args){

Random rnd = new Random();

try{

PrintWriter writer = new PrintWriter("sphere.txt", "UTF-8");

for(int i = 0; i < 1000; i++){

double x = rnd.nextGaussian();

double y = rnd.nextGaussian();

double z = rnd.nextGaussian();

double r = Math.sqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z);

writer.println(x/r + " " + y/r + " " + z/r);

}

}catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace(System.out);

}

}

}

In addition, the saved sphere.txt can be opened with CloudCompare to view point clouds.

The questioner means to make the distance between points on the sphere as large as possible, but uniform random distribution cannot guarantee that two points with an arbitrarily small distance will not appear, so this question has nothing to do with random distribution on the sphere (the title is too confusing).

It’s a long word when it comes to the uniform and random distribution of the sphere. I am puzzled by the magical algorithm given by @lianera earlier. Why use normal distribution? Later, I got a glimpse of the clues from the unitization: Unitization is actually the projection of the volume distribution onto the sphere. Because the normal distribution is spherically symmetric, it must be uniform when projected onto the sphere. In other words, what really matters is the spherical symmetry of the distribution, and the specific form does not matter. For example, if the area within a circle is uniformly distributed and projected, the uniform distribution on the circle can be obtained:

Spherical Codes

After searching online, I found out that this problem has quite a origin. It is called Tamme's problem, and the solution to the problem is called "spherical codes". Here are some calculated results. At the same time, we also know that it is very difficult to find and prove the optimal solution when there are many points.

So the question holder can just find a good sub-optimal solution. The link given by the questioner is actually based on an average stacking strategy: divide the sphere into several circles evenly using lines of latitude, and then divide each circle into equal angles, but there will be fewer points above the circles at high latitudes, and at low latitudes. More.

The most valuable question

To get better results, you can use various optimization toolkits to find the maximum value of the minimum distance between spherical points. If the objective function is directly written in the form of the minimum distance between spherical points, the function will have poor stability and it will be difficult to find the optimal solution. Here, the objective function is taken as the reciprocal sum of the squares of all point spacings and the minimum value is found:

This not only highlights the distance between adjacent points but also keeps the function relatively smooth.

I use the

function provided by

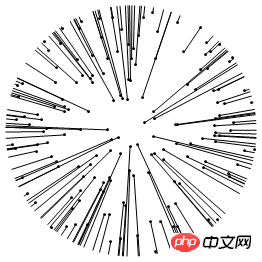

Mathematica. When there are many points, it takes a long time to calculate. For example, it takes four hours to calculate 160 points on my machine. Result drawing: NMinimize

It is not difficult to achieve uniform sampling on a sphere. Just use a normally distributed random variable to generate a three-dimensional vector and then unitize it.

But I don’t know if it meets the requirements between adjacent points. If you want to ensure that adjacent points are far away, you can learn from ideas such as jittering or stratified sampling.

Java version

In addition, the saved sphere.txt can be opened with CloudCompare to view point clouds.The questioner means to make the distance between points on the sphere as large as possible, but uniform random distribution cannot guarantee that two points with an arbitrarily small distance will not appear, so this question has nothing to do with random distribution on the sphere (the title is too confusing).

It’s a long word when it comes to the uniform and random distribution of the sphere. I am puzzled by the magical algorithm given by @lianera earlier. Why use normal distribution? Later, I got a glimpse of the clues from the unitization: Unitization is actually the projection of the volume distribution onto the sphere. Because the normal distribution is spherically symmetric, it must be uniform when projected onto the sphere. In other words, what really matters is the spherical symmetry of the distribution, and the specific form does not matter. For example, if the area within a circle is uniformly distributed and projected, the uniform distribution on the circle can be obtained:

Spherical Codes

After searching online, I found out that this problem has quite a origin. It is called Tamme's problem, and the solution to the problem is called "spherical codes". Here are some calculated results. At the same time, we also know that it is very difficult to find and prove the optimal solution when there are many points.So the question holder can just find a good sub-optimal solution. The link given by the questioner is actually based on an average stacking strategy: divide the sphere into several circles evenly using lines of latitude, and then divide each circle into equal angles, but there will be fewer points above the circles at high latitudes, and at low latitudes. More.

The most valuable question

To get better results, you can use various optimization toolkits to find the maximum value of the minimum distance between spherical points. If the objective function is directly written in the form of the minimum distance between spherical points, the function will have poor stability and it will be difficult to find the optimal solution. Here, the objective function is taken as the reciprocal sum of the squares of all point spacings and the minimum value is found:

$$text{minimize:} quad sum_{ilt{}j}frac{1}{d^2(i,j)}$$

This not only highlights the distance between adjacent points but also keeps the function relatively smooth.

I use the

function provided byMathematica. When there are many points, it takes a long time to calculate. For example, it takes four hours to calculate 160 points on my machine. Result drawing:

NMinimize