…或者換句話說,這是進入嵌入式系統的最愚蠢的方法。

在這裡觀看實際操作!

目標很簡單。用C或C++編寫一些程式碼,並且能夠在Scratch中執行。老實說,我覺得這個想法很有趣:最快的程式語言之一是最慢的程式語言之一。我有一種感覺這是可能的,但我不太確定如何實現。在這個過程中,我學到的關於彙編語言、進程記憶體和可執行檔的知識比我預想的要多得多,我希望你能學到新的東西,同時我也回顧一下我的旅程。

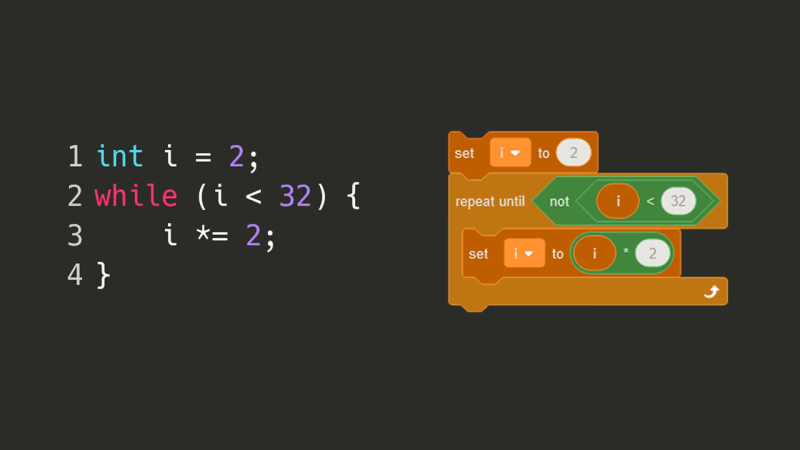

我的第一個想法是把我用 C 寫的程式碼分成幾個部分,然後使用 Scratch 將這些部分重新組合在一起。例如,C 中的 while 迴圈可能會變成 Scratch 中的重複直到區塊:

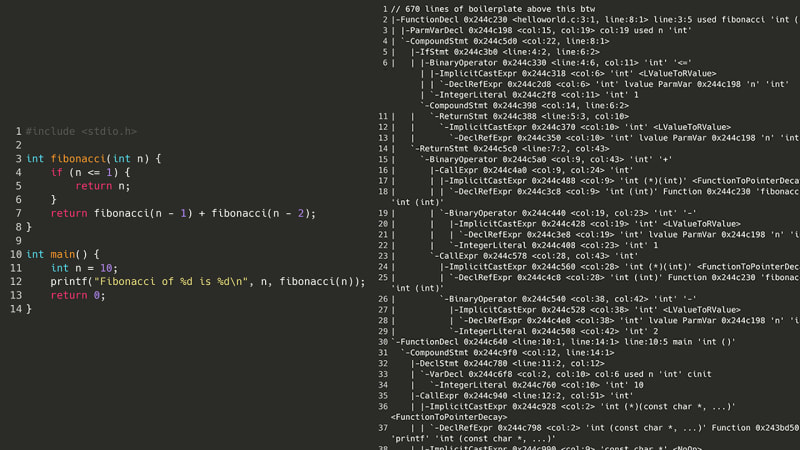

為了讓C編譯器理解程式碼,它首先需要產生一個AST(抽象語法樹),它是原始碼中每個重要符號的樹表示。例如,左括號、變數名稱或 return 關鍵字都可能轉換為不同的節點。然而,在查看了一個簡單的斐波那契數列程式的 AST 之後…

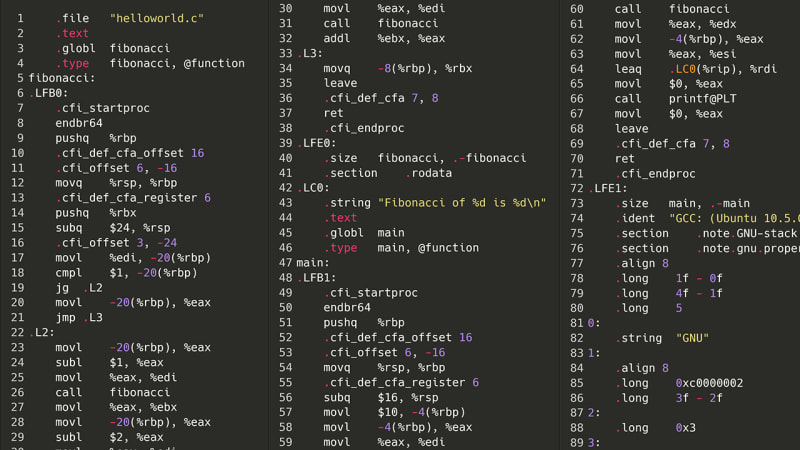

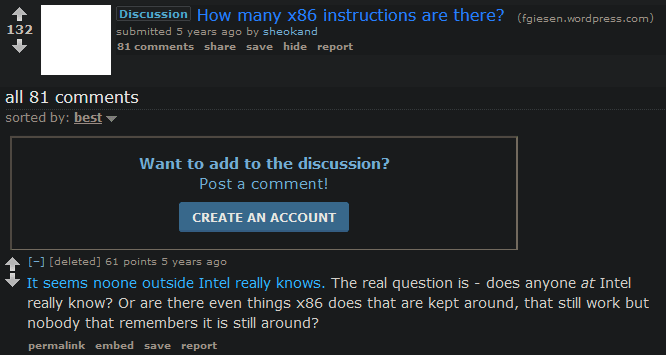

好吧,所以這是不可能的。但是,如果我們不是嘗試重新編譯原始碼,而是沿著階梯往下走一步:彙編呢?為了讓程式運行,首先需要將其編譯為組合語言。在我的計算機上,它是 x86-64asm。由於彙編沒有任何複雜的嵌套結構、類別甚至變量,因此嘗試解析彙編指令列表(理論上)應該比嘗試解析 AST 的意大利麵怪物(例如上面的指令)更容易。這是相同的斐波那契數列,但採用 x86 組譯語言。

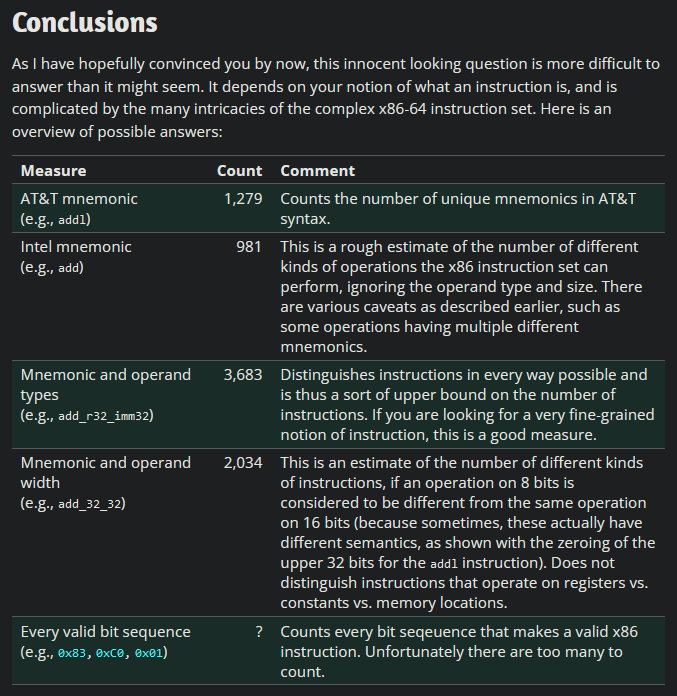

哦,兄弟。好吧,也許情況並沒有那麼糟。總共有多少指令?

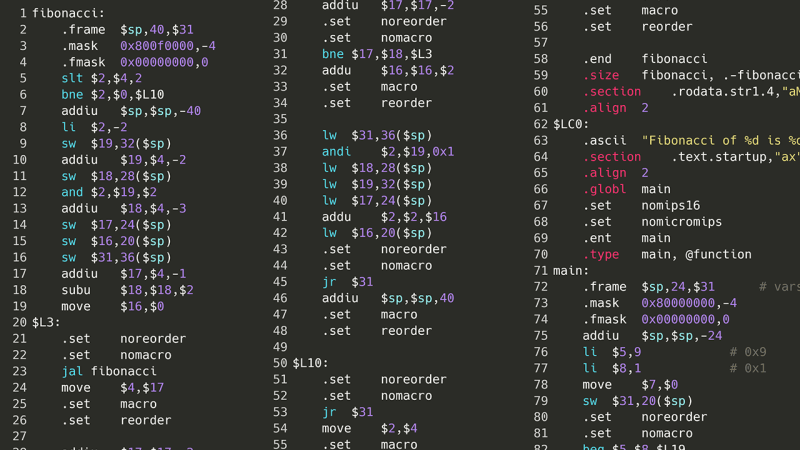

值得慶幸的是,x86 並不是唯一的組合語言。作為大學課程的一部分,我了解了 MIPS,這是一種彙編語言(過度簡化),在 20 世紀 90 年代到 2000 年代初的一些視頻遊戲機和超級電腦中使用,至今仍有一些用途。從 x86 切換到 MIPS 使指令計數從*未知*減少到 50 左右。

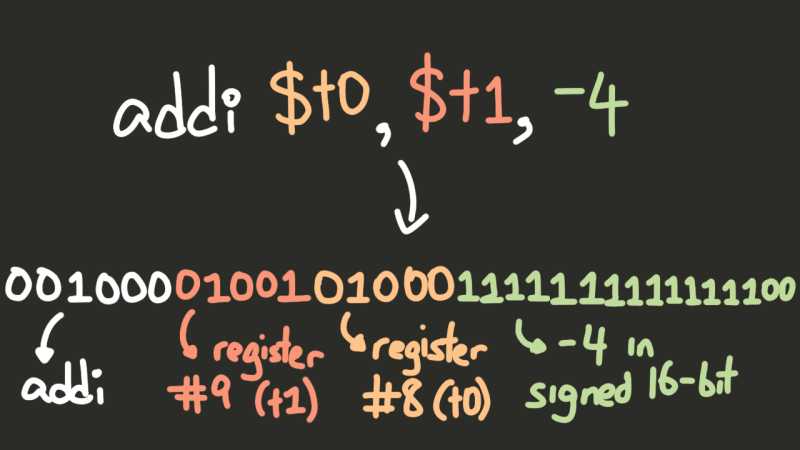

使用 32 位元版本的 MIPS,該彙編程式碼可以轉換為機器碼,其中每條指令都根據處理器架構設定的指導原則轉換為處理器可以理解的 32 位元整數。網路上有一本關於 MIPS 指令集架構的書,所以如果我取得機器碼,然後準確地模擬 MIPS 處理器的功能,那麼我應該能夠在 Scratch 中運行我的 C 程式碼!

現在一切都已經解決了,我們可以開始了。

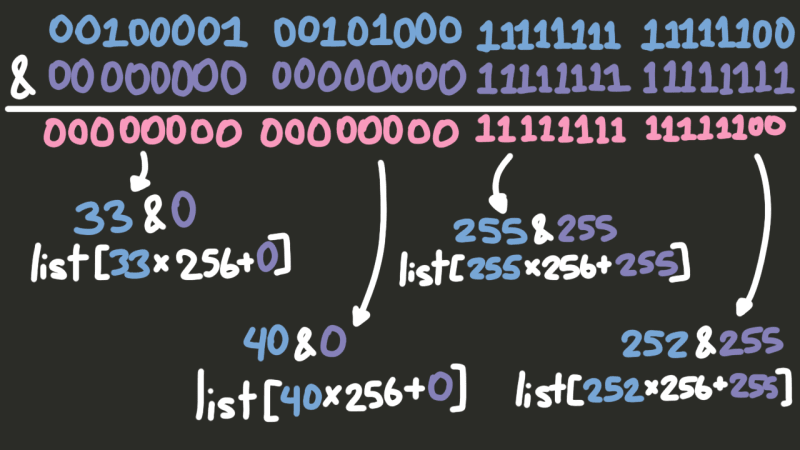

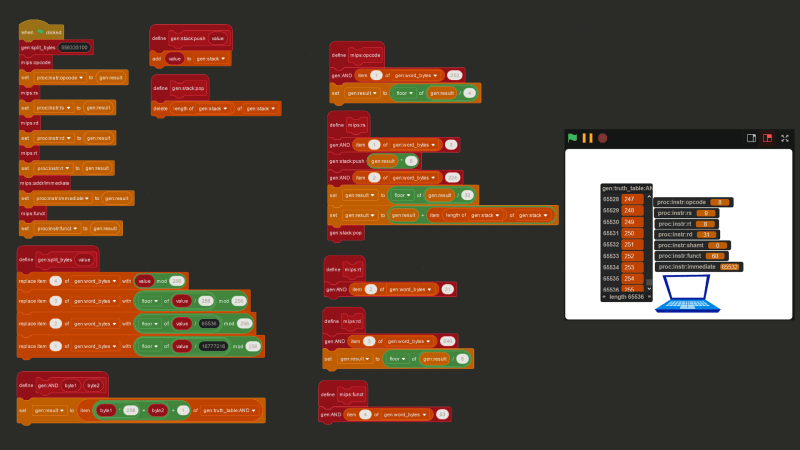

好吧,已經有問題了。通常,如果你有一個整數,並且想要從中提取一系列位,則可以計算 num & mask,其中 mask 是一個整數,其中每個重要位元都是 1,每個不重要位元都是 0。

001000 01001 01000 1111111111111100 & 000000 00000 00000 1111111111111111 -------------------------------------- 000000 0000 000000 1111111111111100

問題? Scratch 中沒有 & 運算子。

現在,我*可以*簡單地逐位檢查這兩個數字,並檢查兩位的四種可能組合中的每一種,但這會非常慢;畢竟,這需要對*每個*指令執行多次。相反,我想出了一個更好的計劃。

首先,我編寫了一個快速的 Python 腳本來計算 0 到 255 之間的每個 x 和每個 y 的 x 和 y。

for x in range(256):

for y in range(256):

print(x & y)

0 (0 & 0 == 0)

0 (0 & 1 == 0)

0 (0 & 2 == 0)

...

0 (0 & 255 == 0)

0 (1 & 0 == 0)

1 (1 & 1 == 1)

0 (1 & 2 == 0)

...

254 (255 & 254 == 254)

255 (255 & 255 == 255)

現在,例如,為了計算兩個 32 位元整數的 x 和 y,我們可以執行以下操作:

Split x and y into four 8-bit integers (or bytes).

Check what first_byte_in_x & first_byte_in_y is by looking in the table generated from the Python script.

Similarly, look up what second_byte_in_x & second_byte_in_y is, and the third bytes, and the fourth bytes.

Take the results of each of these calculations, and put them together to get the result of x & y .

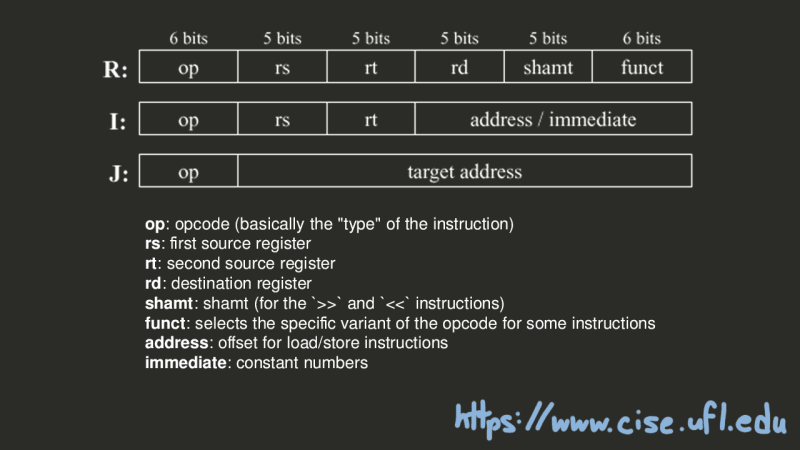

However, once a MIPS instruction has been cut up into four bytes, we’ll only & the bytes we need. For example, if we only need data from the first byte, we won’t even look at the bottom three. But how do we know which bytes we need? Based on the opcode (i.e. the “type”) of an instruction, MIPS will try to split up the bits of an instruction in one of three ways.

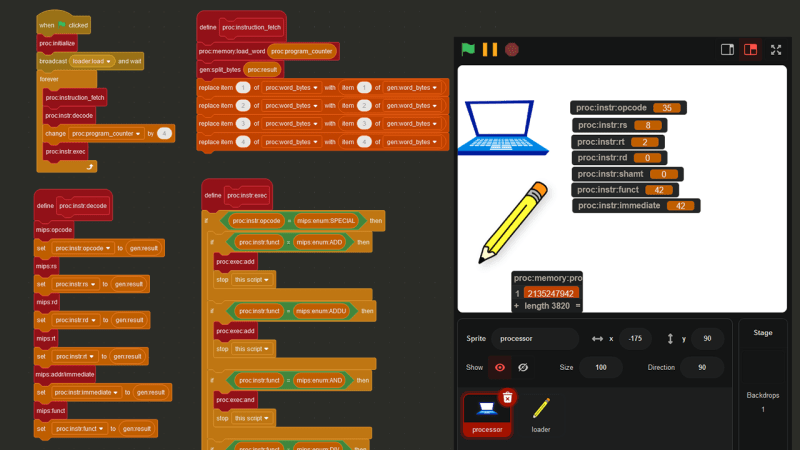

Putting everything together, below is the Scratch code to extract opcode, $rs, $rt, $rd, shamt, funct, and immediate for any instruction.

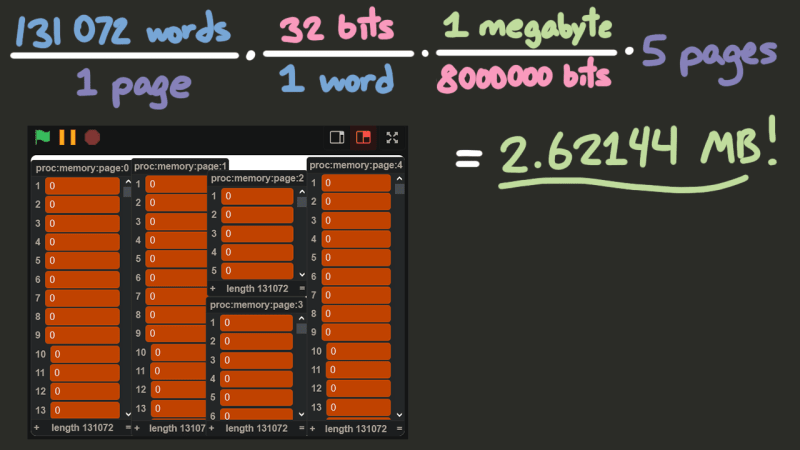

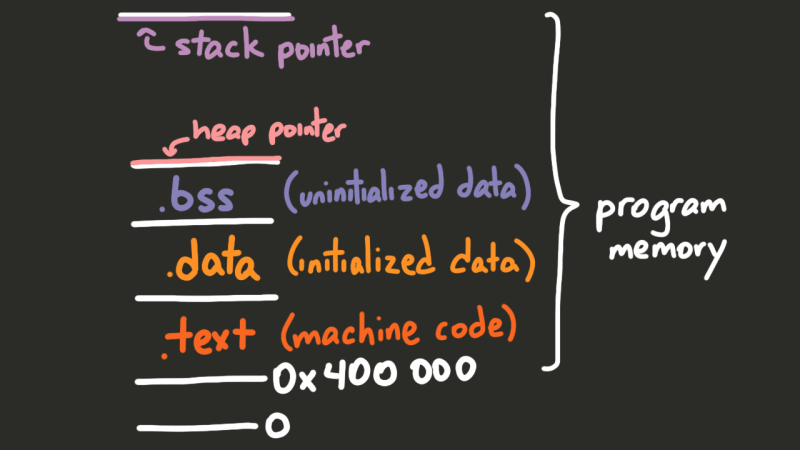

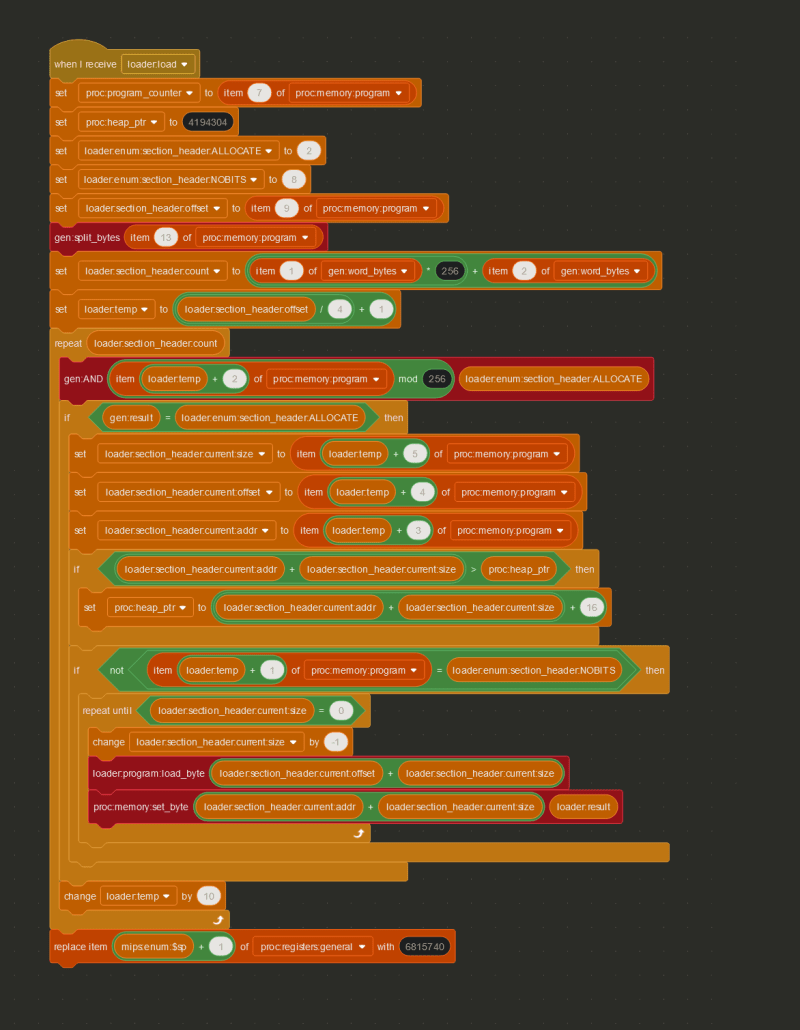

So, how much memory should our processor actually have? And how should we store it? Well, minimum, MIPS processors have 31 general-purpose registers, and one $zero register that is meant to store the number 0 at all times. A register is a location in memory that a processor can access quickly. We can represent these 32 registers as a list with 32 items in Scratch. As for the rest of the memory, simulating a processor moving chunks of data in and out of its cache in Scratch would be pretty pointless and would actually slow things down, rather than speed them up. So instead, the physical memory will be represented as five lists containing 131,072 elements each, where each element will be a 32-bit integer, giving us about 2.6MB of memory. A contiguous block of memory like these lists is usually called a “page”, and the size of the data that the instruction set works with (in this case 32 bits) is usually called a “word”.

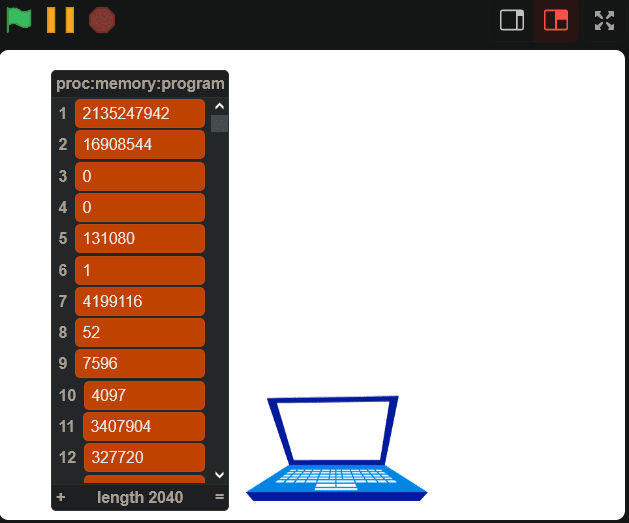

So, how do we get machine code in here? We can’t just import a file into Scratch. But we *can *import text! So, I wrote a program in C to take a binary executable file, and convert every 32 bytes of the file into an integer. C, by default, was reading each byte in little-endian, so I had to introduce a function to flip the endianness. Then, I can save the machine code of a program as a text file (a list of integers), and then import it into my proc:memory:program variable.

#include <stdio.h>

unsigned int flip_endian(unsigned int value) {

return ((value >> 24) & 0xff) | ((value >> 8) & 0xff00) | ((value << 8) & 0xff0000) | ((value << 24) & 0xff000000);

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

if (argc != 3 && argc != 2) {

printf("Usage: %s <input file> <output file?>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

FILE* in = fopen(argv[1], "r");

if (!in) {

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

unsigned int value;

FILE* out = argc == 3 ? fopen(argv[2], "w") : stdout;

if (!out) {

perror("fopen");

return 1;

}

while (fread(&value, sizeof(value), 1, in) == 1) {

fprintf(out, "%u\n", flip_endian(value));

}

fclose(in);

if (out != stdout) {

fclose(out);

}

return 0;

}

Okay, so now that we can import the data into Scratch, we can just set the program counter (the integer keeping track of the current instruction) to the top of the list, and start executing instructions, right?

Wrong.

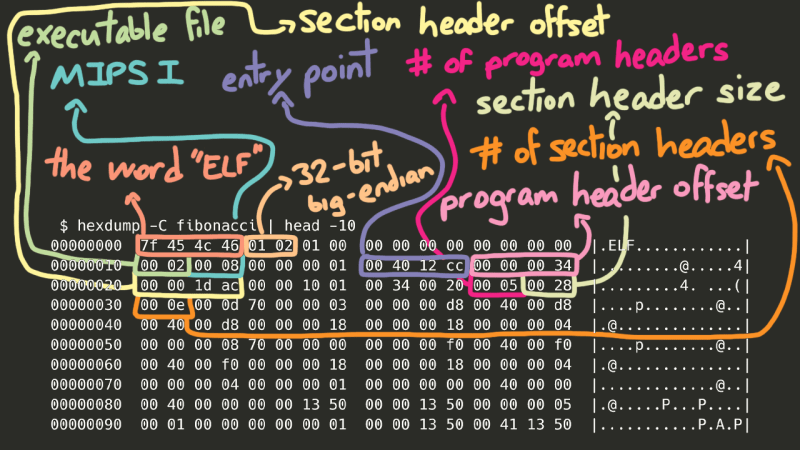

I didn’t realize this going into this project, but the first several bytes of an executable file *aren’t *instructions, but a header identifying what type of executable file it is. On Windows, it’ll usually be the PE, or Portable Executable, format, and on UNIX-based systems (the version we’ll be using) it’ll be the ELF format. So, how do we actually know where the code starts? On Linux, we can use the builtin readelf utility to actually see what’s in the ELF header, and the Linux Foundation has a page detailing the ELF header standard. So, we can use the LF page to figure out which bytes mean what, and the readelf command to “check our work”.

$ readelf -h fibonacci ELF Header: Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 01 02 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 Class: ELF32 Data: 2's complement, big endian Version: 1 (current) OS/ABI: UNIX - System V ABI Version: 0 Type: EXEC (Executable file) Machine: MIPS R3000 Version: 0x1 Entry point address: 0x4012cc Start of program headers: 52 (bytes into file) Start of section headers: 7596 (bytes into file) Flags: 0x1001, noreorder, o32, mips1 Size of this header: 52 (bytes) Size of program headers: 32 (bytes) Number of program headers: 5 Size of section headers: 40 (bytes) Number of section headers: 14 Section header string table index: 13

Now, there’s a lot of really interesting stuff here, but to save some time, the *really *important data here (besides the entry point, of course) are the section headers. Oversimplifying greatly, in order for our program to run correctly, we need to take certain chunks of the file and place them in certain parts of memory so our code can access them.

Using the readelf utility, we can actually see all of the sections in the file:

$ readelf -S fibonacci There are 14 section headers, starting at offset 0x1dac: Section Headers: [Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al [ 0] NULL 00000000 000000 000000 00 0 0 0 [ 1] .MIPS.abiflags MIPS_ABIFLAGS 004000d8 0000d8 000018 18 A 0 0 8 [ 2] .reginfo MIPS_REGINFO 004000f0 0000f0 000018 18 A 0 0 4 [ 3] .note.gnu.build-i NOTE 00400108 000108 000024 00 A 0 0 4 [ 4] .text PROGBITS 00400130 000130 001200 00 AX 0 0 16 [ 5] .rodata PROGBITS 00401330 001330 000020 00 A 0 0 16 [ 6] .bss NOBITS 00411350 001350 000010 00 WA 0 0 16 [ 7] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 001350 000029 01 MS 0 0 1 [ 8] .pdr PROGBITS 00000000 00137c 000440 00 0 0 4 [ 9] .gnu.attributes GNU_ATTRIBUTES 00000000 0017bc 000010 00 0 0 1 [10] .mdebug.abi32 PROGBITS 00000000 0017cc 000000 00 0 0 1 [11] .symtab SYMTAB 00000000 0017cc 000380 10 12 14 4 [12] .strtab STRTAB 00000000 001b4c 0001db 00 0 0 1 [13] .shstrtab STRTAB 00000000 001d27 000085 00 0 0 1 Key to Flags: W (write), A (alloc), X (execute), M (merge), S (strings), I (info), L (link order), O (extra OS processing required), G (group), T (TLS), C (compressed), x (unknown), o (OS specific), E (exclude), p (processor specific)

Going through all the details of the ELF format could be its own multi-part write-up, but using the Linux Foundation page on section headers, I was able to decipher the section header bytes of the program, and copy all the important bytes from the proc:memory:program variable to the correct places in memory, by checking whether or not the section header had the ALLOCATE flag set.

Fast-forwarding about a week to the point where all of the important instructions have been implemented, let’s take a look at the steps the processor (or really, any processor) needs to take in order to understand just one instruction, using 0x8D02002A (2365718570) as an example.

The first step is called **INSTRUCTION FETCH. **The current instruction is retrieved from the address stored in the proc:program_counter variable.

The next step is INSTRUCTION DECODE, where the instruction is decoded into its separate parts (see Step 1).

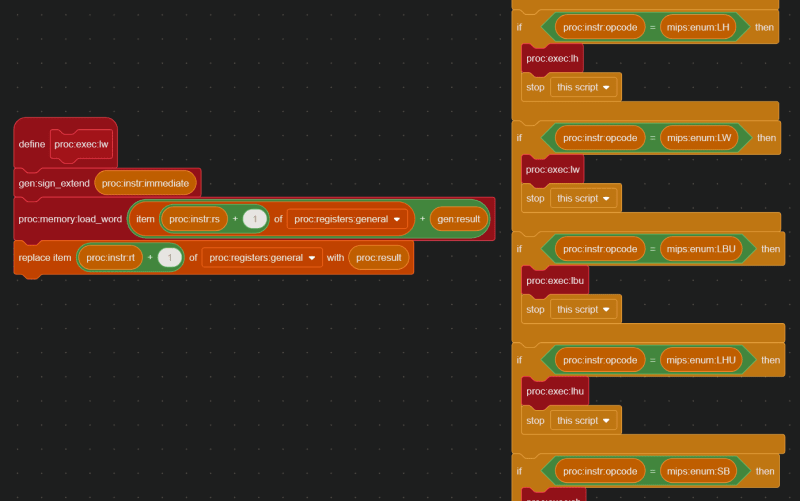

Finally, we reach EXECUTE, which, in my Scratch processor, is pretty much just a big if statement.

In this case, the INSTRUCTION DECODE step revealed that the opcode is 35, which means 0x8D02002A is a lw (load word) instruction. Therefore, based off the values in proc:instr:rs, proc:instr:rt, and proc:instr:immediate, the instruction 0x8D02002A actually means lw $2, 0x2a($8) , or in other words, lw $v0, 42($t0).

And here is the code that handles the lw instruction:

Okay, home stretch. Now, we just need to be able to do the bare minimum and create a “Hello, World” program in C, and run it in Scratch, and the last two weeks of my life will have been validated.

So, will this work?

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

Three changes. First of all, the MIPS linker uses start to find the entry point of the program, much the same way you use main in C, or "main__" in Python. So, that’s an easy fix.

#include <stdio.h>

int __start() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}

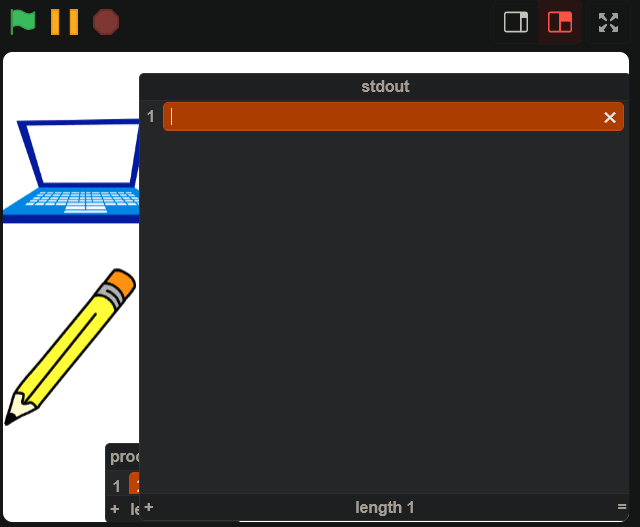

Next, we need some way to actually see this output in Scratch. We *could *make some intricate array of text sprites, but the simpler solution is just to use a list.

Finally, we can’t use stdio.h.

Yeah, basically, implementing floating point registers and multiprocessor instructions would have been more trouble than it was worth, so I skipped it, but the standard library kind of expects all that to be there. So, we need to make printf ourselves.

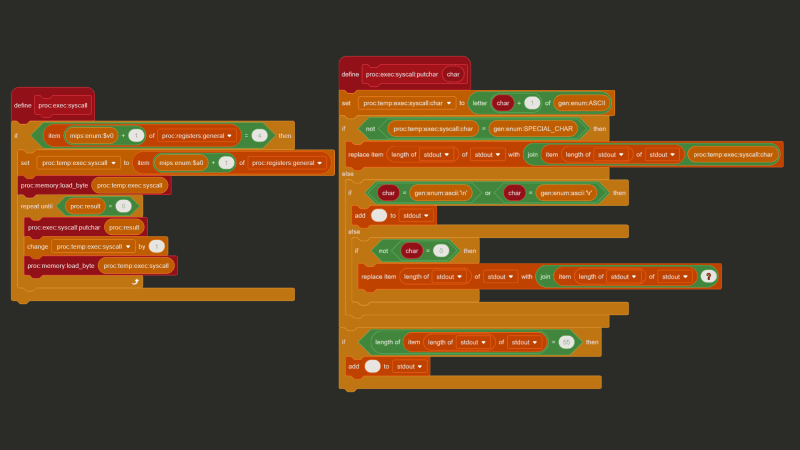

Putting the complications of variadic arguments and text formatting aside, how can you actually print a string using MIPS? The TL;DR is you put the address of the string in a certain register, and then a special “print string” value in another register, and then execute the syscall (“system call”) instruction, and let the OS/CPU handle the rest.

The exact special values and registers to use are implementation-dependent, and can be implemented pretty much any way you see fit, but I chose to replicate MARS’ (a very popular MIPS simulator) implementation. With MARS, the address of the string goes in $a0, and the value 4 goes in $v0 to say “hey, I want to print a string!”

And with C, we can use a feature called “inline assembly” to inject assembly code directly into our compiled output. Putting it all together we get this:

#define puts _puts

void _puts(const char *s) {

__asm__(

"li $v0, 4\n"

"syscall\n"

:

: "a"(s)

);

}

int __start() {

puts("Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

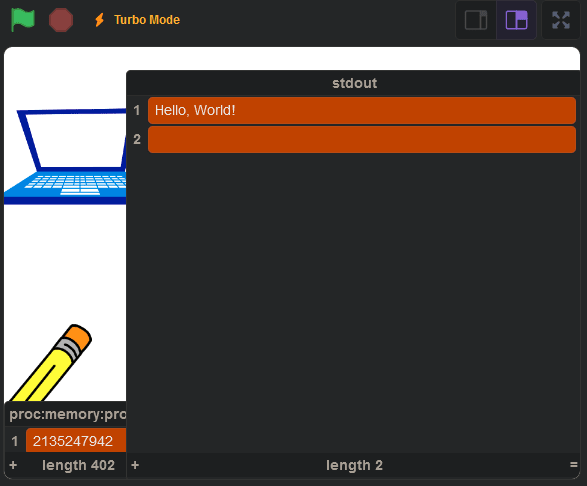

And when we run it, we get this:

You can view the final product here: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/1000840481/.

I wanted to keep this read under 15 minutes, so I had to skip over **a lot **of details. Some parts of the Scratch code had to be cut out of the screenshots for simplicity’s sake and I ran into a lot of silly and not-so-silly mistakes. If you’re curious how I was able to get Connect Four working (with minimax and alpha-beta pruning), the source code is on my Github. Here’s a quick list of some of the other problems I ran into in development:

* The fact that my computer is little-endian, but MIPS is big-endian caused more issues than I'd like to admit * The `mult` instruction in MIPS is 32-bit multiplication, and multiplying two 32-bit integers can result in a 64-bit integer. Javascript (and as a result, Scratch) is incapable of storing a 64-bit integer without losing precision. * The `u` in the `addu` instruction and the `u` in the `sltu` instruction both stand for "unsigned", but mean completely different things. * As you may have noticed, functions in Scratch don't have return values. This was quite annoying. * Any branch instruction (like "jump", "jump register", "branch on equals") in MIPS will also execute the instruction immediately after it, **regardless** of if the branch was taken or not. So, instead of updating the program count directly, the next address needs to be put in the "branch delay slot" and the program counter should only be updated after the *next* instruction. * Lists in Scratch are one-indexed. * All of a sudden, Scratch stopped letting me save the project to the cloud. It took awhile before I realized that lists filled with over 100,000 items wasn't something Scratch's servers were particularly excited to store. * I had to design my own `malloc` in C, which was fun, but also very difficult to debug in Scratch. * When I tried making syscalls that asked the user for input, all of the letters ended up capitalized. It turns out that in Scratch a lowercase `"a"` and a capital `"A"` are considered equal. I thought this was an unsolvable problem for awhile, before I realized that the names of sprites' costumes in Scratch are actually case-sensitive. So every time I try to convert a character to its ASCII value, I tell the processor sprite to switch to, for example, the `"a"` costume or the `"A"` costume, and then retrieve the costume number. * I made another syscall to print emojis to the `stdout`, but some emojis are considered two characters long and other emojis are considered one character long. * Compiling any code that calls `malloc` with -O1 crashes the CPU. I still have no idea why this is the case. * Endianness is really hard to get right. I know I said this in the beginning of the list, but it's worth repeating.

With all that said, I’m really happy with the way this project turned out. If you found this interesting, please check out sharc, my graphics engine built completely in Typescript: https://www.sharcjs.org. Because clearly, if there’s one thing I know how to make, it’s questionable decisions.

以上是用兒童程式語言建構計算機的詳細內容。更多資訊請關注PHP中文網其他相關文章!