這篇文章是關於 Go 中處理並發的系列文章的一部分:

WaitGroup 基本上是一種等待多個 goroutine 完成其工作的方法。

每個同步原語都有自己的一系列問題,這也不例外。我們將重點放在 WaitGroup 的對齊問題,這就是為什麼它的內部結構在不同版本中變化的原因。

本文以 Go 1.23 為基礎。如果後續有任何變化,請隨時透過 X(@func25) 告訴我。

如果您已經熟悉sync.WaitGroup,請隨意跳過。

讓我們先深入探討這個問題,想像您手上有一項艱鉅的工作,因此您決定將其分解為可以同時運行且彼此不依賴的較小任務。

為了解決這個問題,我們使用 goroutine,因為它們讓這些較小的任務同時運行:

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func(i int) {

fmt.Println("Task", i)

}(i)

}

fmt.Println("Done")

}

// Output:

// Done

但是事情是這樣的,很有可能主協程在其他協程完成工作之前完成並退出。

當我們分出許多 goroutine 來做他們的事情時,我們希望跟踪它們,以便主 goroutine 不會在其他人完成之前完成並退出。這就是 WaitGroup 發揮作用的地方。每次我們的一個 goroutine 完成其任務時,它都會讓 WaitGroup 知道。

一旦所有 goroutine 都簽入為“完成”,主 goroutine 就知道可以安全完成,並且一切都會整齊地結束。

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(10)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func(i int) {

defer wg.Done()

fmt.Println("Task", i)

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Done")

}

// Output:

// Task 0

// Task 1

// Task 2

// Task 3

// Task 4

// Task 5

// Task 6

// Task 7

// Task 8

// Task 9

// Done

所以,通常是這樣的:

通常,你會看到在啟動 goroutine 時使用 WaitGroup.Add(1):

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

這兩種方法在技術上都很好,但是使用 wg.Add(1) 會對效能造成很小的影響。儘管如此,與使用 wg.Add(n).

相比,它更不容易出錯「為什麼 wg.Add(n) 被認為容易出錯?」

重點是,如果循環的邏輯發生變化,就像有人添加了跳過某些迭代的 continue 語句,事情可能會變得混亂:

wg.Add(10)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

if someCondition(i) {

continue

}

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

在這個例子中,我們在循環之前使用 wg.Add(n) ,假設循環總是恰好啟動 n 個 goroutine。

但是如果這個假設不成立,例如跳過一些迭代,你的程式可能會陷入等待從未啟動的 goroutine 的狀態。老實說,這種錯誤追蹤起來確實很痛苦。

這種情況下,wg.Add(1) 比較合適。它可能會帶來一點點效能開銷,但它比處理人為錯誤開銷要好得多。

人們在使用sync.WaitGroup時也常犯一個很常見的錯誤:

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

go func() {

wg.Add(1)

defer wg.Done()

...

}()

}

歸根結底,wg.Add(1) 正在內部 goroutine 中呼叫。這可能是一個問題,因為 Goroutine 可能在主 Goroutine 已經調用 wg.Wait() 之後開始運行。

這可能會導致各種計時問題。另外,如果您注意到,上面的所有範例都使用 defer 和 wg.Done()。它確實應該與 defer 一起使用,以避免多個返迴路徑或恐慌恢復的問題,確保它總是被呼叫並且不會無限期地阻止呼叫者。

這應該涵蓋所有基礎知識。

我們先查看sync.WaitGroup的原始碼。您會在sync.Mutex 中註意到類似的模式。

再次強調,如果您不熟悉互斥鎖的工作原理,我強烈建議您先查看這篇文章:Go Sync Mutex:正常模式和飢餓模式。

type WaitGroup struct {

noCopy noCopy

state atomic.Uint64

sema uint32

}

type noCopy struct{}

func (*noCopy) Lock() {}

func (*noCopy) Unlock() {}

在 Go 中,只需將結構分配給另一個變數即可輕鬆複製結構。但有些結構,例如 WaitGroup,確實不應該被複製。

Copying a WaitGroup can mess things up because the internal state that tracks the goroutines and their synchronization can get out of sync between the copies. If you've read the mutex post, you'll get the idea, imagine what could go wrong if we copied the internal state of a mutex.

The same kind of issues can happen with WaitGroup.

The noCopy struct is included in WaitGroup as a way to help prevent copying mistakes, not by throwing errors, but by serving as a warning. It was contributed by Aliaksandr Valialkin, CTO of VictoriaMetrics, and was introduced in change #22015.

The noCopy struct doesn't actually affect how your program runs. Instead, it acts as a marker that tools like go vet can pick up on to detect when a struct has been copied in a way that it shouldn't be.

type noCopy struct{}

func (*noCopy) Lock() {}

func (*noCopy) Unlock() {}

Its structure is super simple:

When you run go vet on your code, it checks to see if any structs with a noCopy field, like WaitGroup, have been copied in a way that could cause issues.

It will throw an error to let you know there might be a problem. This gives you a heads-up to fix it before it turns into a bug:

func main() {

var a sync.WaitGroup

b := a

fmt.Println(a, b)

}

// go vet:

// assignment copies lock value to b: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

// call of fmt.Println copies lock value: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

// call of fmt.Println copies lock value: sync.WaitGroup contains sync.noCopy

In this case, go vet will warn you about 3 different spots where the copying happens. You can try it yourself at: Go Playground.

Note that it's purely a safeguard for when we're writing and testing our code, we can still run it like normal.

The state of a WaitGroup is stored in an atomic.Uint64 variable. You might have guessed this if you've read the mutex post, there are several things packed into this single value.

Here's how it breaks down:

Then there's the final field, sema uint32, which is an internal semaphore managed by the Go runtime.

when a goroutine calls wg.Wait() and the counter isn't zero, it increases the waiter count and then blocks by calling runtime_Semacquire(&wg.sema). This function call puts the goroutine to sleep until it gets woken up by a corresponding runtime_Semrelease(&wg.sema) call.

We'll dive deeper into this in another article, but for now, I want to focus on the alignment issues.

I know, talking about history might seem dull, especially when you just want to get to the point. But trust me, knowing the past is the best way to understand where we are now.

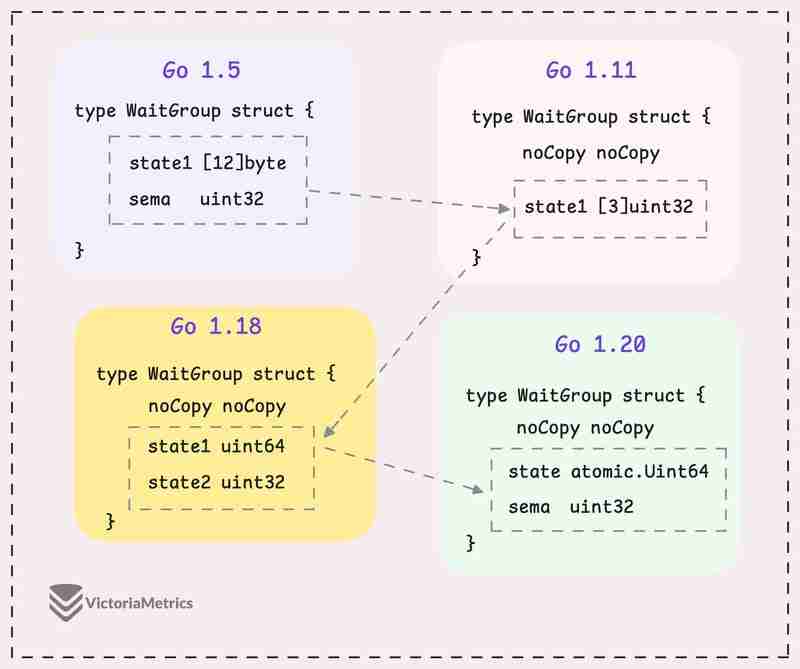

Let's take a quick look at how WaitGroup has evolved over several Go versions:

I can tell you, the core of WaitGroup (the counter, waiter, and semaphore) hasn't really changed across different Go versions. However, the way these elements are structured has been modified many times.

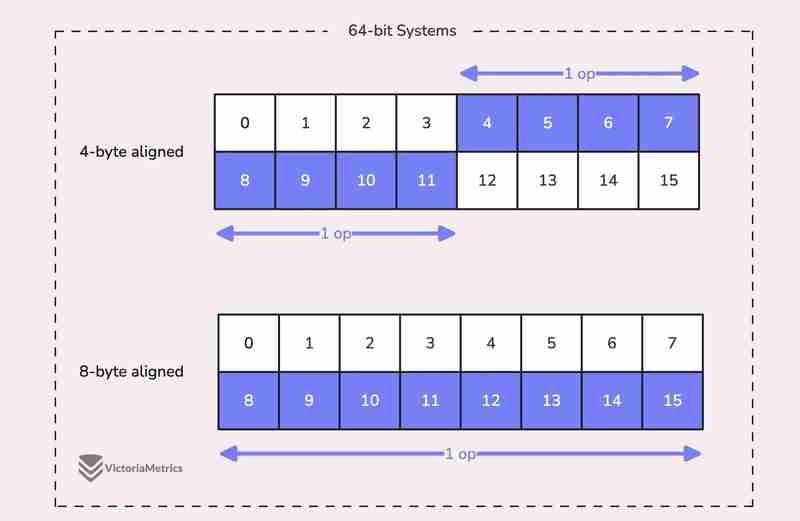

When we talk about alignment, we're referring to the need for data types to be stored at specific memory addresses to allow for efficient access.

For example, on a 64-bit system, a 64-bit value like uint64 should ideally be stored at a memory address that's a multiple of 8 bytes. The reason is, the CPU can grab aligned data in one go, but if the data isn't aligned, it might take multiple operations to access it.

Now, here's where things get tricky:

On 32-bit architectures, the compiler doesn't guarantee that 64-bit values will be aligned on an 8-byte boundary. Instead, they might only be aligned on a 4-byte boundary.

This becomes a problem when we use the atomic package to perform operations on the state variable. The atomic package specifically notes:

"On ARM, 386, and 32-bit MIPS, it is the caller's responsibility to arrange for 64-bit alignment of 64-bit words accessed atomically via the primitive atomic functions." - atomic package note

What this means is that if we don't align the state uint64 variable to an 8-byte boundary on these 32-bit architectures, it could cause the program to crash.

So, what's the fix? Let's take a look at how this has been handled across different versions.

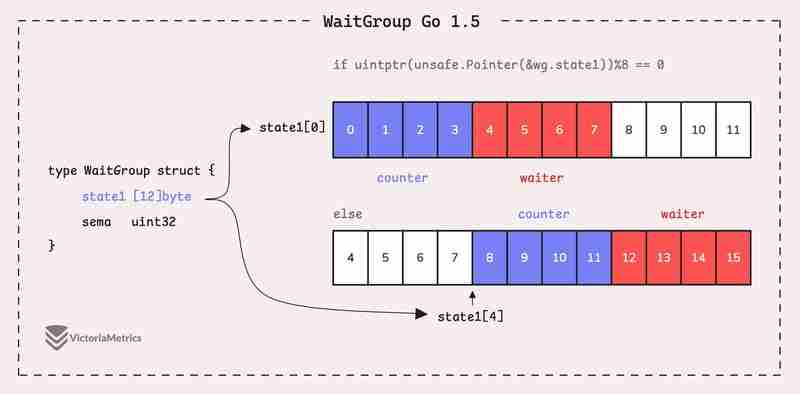

Go 1.5: state1 [12]byte

I'd recommend taking a moment to guess the underlying logic of this solution as you read the code below, then we'll walk through it together.

type WaitGroup struct {

state1 [12]byte

sema uint32

}

func (wg *WaitGroup) state() *uint64 {

if uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))%8 == 0 {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1))

} else {

return (*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&wg.state1[4]))

}

}

Instead of directly using a uint64 for state, WaitGroup sets aside 12 bytes in an array (state1 [12]byte). This might seem like more than you'd need, but there's a reason behind it.

The purpose of using 12 bytes is to ensure there's enough room to find an 8-byte segment that's properly aligned.

The full post is available here: https://victoriametrics.com/blog/go-sync-waitgroup/

以上是Gosync.WaitGroup 與對齊問題的詳細內容。更多資訊請關注PHP中文網其他相關文章!